Presentation by: Dr Nonja Peters

Date: 18 October 2011

Venue: Maritime Archeological Association of Western Australia

How did the earth’s peoples, cultures, economies, and polities become so closely interconnected? When did our world become ‘global’ and what vital role did Asia and Africa play at the centre of this new international community? In this paper I present some snapshots of the establishment of the Dutch East India Company, its operations in Asia and influence in pre-British WA.

The Verenigde Oost Indische Compagnie (VOC)

The VOC was created in 1602 from a fusion of six small companies. Directly after the ‘eerste schipvaart‘ (first fleet) of 1595-1597, which had been organized by the Compagnie van Verre of Amsterdam to demonstrate the possibilities of Asian trade.

Companies were subsequently set up in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Zeeland. And although these companies only accumulated capital for one expedition at a time, there was continuity in the board of directors. The merchants in charge or the bewindhebbers (directors) sponsored successive expeditions. Each time the ships returned from Asia the investors, who included not only the board but also other shareholders or participanten, got back the capital they had subscribed, and a share in the profit. These companies competed fiercely with each other, which put pressure on the profit margins. The dwindling returns threatened to frighten off investors and to endanger the future of the trade with Asia.

The unification (fusion) of the voorcompagnieën (pre-companies) into one company was enforced by the States of Holland under the guidance of Johan van Oldenbarneveldt and the States General. The Dutch Republic was at war with the king of Spain and Portugal and One united Company could be a powerful military and economic weapon in the conflict.

On 20th March 1602, after the intervention of the stadhouder, Prince Maurits, to get the Zeelanders on board, the States General granted the charter by which the Generale Vereenichde Geoctroyeerde Compagnie (General United Chartered Company) was created.

The seventy-six directors who had headed the voorcompagnieën were placed in control of the new company. The charter that established the VOC’s trade monopoly – provisionally for twenty-one years – also altered the position of the directors. They now formed a real board, a managerial group with its own aims, distinct from those of the shareholders. Moreover, rivalry was now out of the question: the charter laid down that nobody except the VOC could send ships from The Netherlands to conduct trade in the octrooigebied (trade zone).

Under the charter the voorcompagnieën became departments or kamers (chambers) in the united Company. There were six of them: Amsterdam, Zeeland (Middelburg), Delft, Rotterdam, Hoorn and Enkhuizen. Agreement then had to be reached about the share of the chambers in the joint shipping and trade to Asia. The Amsterdam Chamber was apportioned half of all operations, Zeeland a quarter and each of the four remaining smaller chambers were allocated one-sixteenth each. The Zeelanders were reassured by this system of distribution which was laid down in the charter; they had feared that, should the capital deposited by the chambers have been taken as the basis for the share in the management of the business, Amsterdam would have won more than half.

Directors became board members of the chambers as a matter of course. A general board, which was to be put in charge of the general management and was to consist of representatives of the directors of the chambers, was placed above the chambers. The consensus that was reached over the proportional relationships between the chambers, settled for seventeen members. In it Amsterdam would be represented by eight directors, Zeeland by four and the smaller chambers would have one each, while the seventeenth member would be appointed in turn by one of the chambers other than Amsterdam.

Directors were of course themselves important investors and, as such, their position and interests did not differ from those of the other shareholders. But as managers they strove to increase the turnover, and for continuity and consolidation, rather than for any short-term profit, which would give the investors a quick return on their investment. In this the directors enjoyed the protection of the charter. Only after ten years, thus after the expiry of the first decennial capital account, were they required to open the books and to account to the shareholders. Directorship was for life. Shareholders had no influence at all on the appointment of new directors. Directors were supposed to have shares in the VOC set at a fixed minimum amount: fl. 6,000 (in the chambers of Hoorn and Enkhuizen fl. 3,000).[1]

The he charter fixed the number of directors at sixty: twenty in the Amsterdam Chamber, twelve in that of Zeeland and seven in each of the smaller chambers. It also fixed the way that capital could be acquired. The incomes of the directors was also fixed by it at one per cent of the expenditure on the outfitting or equipages and at one per cent of the profits from the sale of the retourgoederen (return wares).

Multinational – Stocks and Shares – share trading

Two criteria acquired the Dutch East India Company (VOC) the nomenclature – multinational, or world’s first mega-corporation:

- it issued shares: While trade exchanges were common in medieval Europe, these were typically for currency, commodities and bonds – not shares. In fact by 1669, its shares were bringing a 40% return.[2] However, buyers of VOC shares could not cash them in, only sell them on – and so share trading was born. Many investors were employees, including humble carpenters and bakers. In the early days they were paid their dividends partly in cash and partly in spices – pepper, mace, or nutmeg. Expensive items are often still referred to as being perduur (as costly as pepper).[3]; and

- it operated in more than one country. Between 1602- 1796, it sent some 4,785 ships to various ports throughout Asia (Lost ships 653?).

The VOC’s Influence in Asia

The ‘octrooi’ (charter) gave the VOC not only monopoly over Asian trade in its name in the octrooigebied (trade zone between South Africa and Japan it also gave them quasi-governmental powers to erect fortifications, employ soldiers; conclude treaties with Asian rulers; keep a standing army, and appoint Governors and judges.

The first fleets sent out by the VOC after 1602 were much more heavily armed than the ships of the voorcompagnieën had been to particularly inflict maximum damage on the Portuguese.

Even so by 1609 the Directors were emulating the Portuguese centralized power structure by placing the supreme command in Asia in the hands of a Governor-General, with the assistance of the Raad van Indië (Council of the Indies).[4]

The founding of Batavia in 1619 on the site of the Javanese harbour town of Jakatra was the next logical step. It became the seat of the Governor-General and Council, administrative centre and rendez-vous for the Company’s shipping traffic.

European trading communities sprang up all over Asia alongside those of the Chinese, the Javanese, Tamils, Gujaratis, Armenians and others. Adapting quickly, the Europeans learned the commercial lingua franca of the area and mastered the rules of the local market. They entered into (temporary) relations with local women, and many trading posts were soon peppered with their offspring. Most of these children remained in the country of their birth and were subsumed into the local community or else entered the service of the European merchants and companies. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) made good use of such people, born and brought up locally, they could speak the language of their birth country and understood the conventions. As such they proved excellent middlemen for the Europeans. For the same reason, these Eurasians were also extremely useful to the Asian rulers (Bosma and Rabin 2008:9).

The VOC enjoyed huge profits from its spice monopoly through most of the 1600s. Cape Town and the Cape Colony played an important role. Established by Jan Reebeck in 1652 it produced the fresh supplies needed to cross the Indian Ocean to the Spice Islands. However, before long it also sported a hospital for mariners who had taken ill on VOC journeys. Here they could recoup until well enough to continue onwards. Cape Town also built a garrison for soldiers. It provided many VOC ships who had lost mariners and soldiers en-route with the top-ups required to complete the journey.[5]

The VOC eclipsed all of its rivals in the Asia trade. Between 1602 and 1796 their ships carried almost a million Europeans to work in Asian trade. Their efforts netted more than 2.5 million tons of Asian trade goods. By contrast, the rest of Europe combined sent only 882,412 people from 1500 to 1795, and the fleet of the English (later British) East India Company, the VOC’s nearest competitor, was a distant second to its total traffic with 2,690 ships and a mere one-fifth the tonnage of goods carried by the VOC.

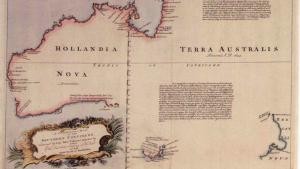

VOC in Australia

The Dutch connection with Australia that began in March 1606 – thus before the Pilgrim Father’s went to America (Leiden) – in Wik country near what is now Weipa in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Qeensland, by Willem Jansen, skipper of the Duyfken a Jacht of the Dutch East India Company (Vereinigde Oost Indisch Compagnie VOC) and his crew, looking for trading opportunities. While doing so they mapped 250 kilometres of the coastline to Cape Keerweer.[6]

The Dutch connection with Australia that began in March 1606 – thus before the Pilgrim Father’s went to America (Leiden) – in Wik country near what is now Weipa in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Qeensland, by Willem Jansen, skipper of the Duyfken a Jacht of the Dutch East India Company (Vereinigde Oost Indisch Compagnie VOC) and his crew, looking for trading opportunities. While doing so they mapped 250 kilometres of the coastline to Cape Keerweer.[6]

All told, around 30 mariners including Abel Tasman, Baudan, Freycinyet and others from diverse national backgrounds mapped parts of the Southland’s coastline before Captain James Cook declared it British territory.[7]

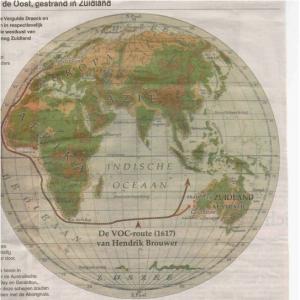

It was therefore the Mariners, merchants and passengers on ships belonging to the VOC, who were the first recorded Europeans to step foot on Australian soil. Mainly by chance, while in pursuit of the spice trade, and largely because the instruments used to determine longitude were still in their infancy. There arrival in WA was a consequence of the introduction in of Brouwer’s new route in 1617. Ships that left Cape Town for the East Indies were then directed to utilise the “Roaring Forties Trade Winds”.

The advantage of the change in direction was a shorter cooler journey and therefore less illness, fewer deaths and food remained unspoiled longer. A disadvantage was ships either encountering or coming to grief on the coast of Western Australia. The first being Dirk Hartog in the Eendracht in 1616. Famous ships wrecks are the Batavia (1629), Gilt Dragon (1656), Zuytdorp (1712) and Zeewijk (1727). Perhaps we may still find the wrecks of the Zeelt (1672), Ridderschap van Holland (1694), the Fortuyn (1724) and the Aaagtekerke (1726).

Estimates suggest a possible 200 people were marooned permanently on the WA coast from the Batavia, Gilt Dragon and Zuytdorp shipwrecks and the crews and landing parties on long boats sent to find them who were abandoned on shore when the weather turned stormy (See table one).[8]

Estimates suggest a possible 200 people were marooned permanently on the WA coast from the Batavia, Gilt Dragon and Zuytdorp shipwrecks and the crews and landing parties on long boats sent to find them who were abandoned on shore when the weather turned stormy (See table one).[8]

Aboriginal oral history has it that the fortunate ones cohabited with the local Aboriginal people. Evidence compelling enough to fire the imagination but not to fix as fact links the fate of those marooned when the Gilt Dragon sank near Lancelin to the Noongar (Yuat, Wadjuk and Belardang) people; and survivors of the Zuytdorp to the Nanda, Malgana and Wadjarri peoples. It is possible but less probable that those from the Batavia, Sardam and Goede Hoop may also have ended their lives with indigenous Australians.[9] This is supported by Nanda oral history which also claims one or more of the many castaways fathered children with Aboriginal mothers. VOC ships stopped visiting WA shores when the world’s first multinational company collapsed in 1796.

Several reports over many years attest to some Aborigines in the region having fair skin and European facial features. Two diseases Porphyria varigata and Ellis van Creveld, which has a high incidence among Western Australian Aborigines and also the Old Order Amish are associated with the possible cohabitation. Both these syndromes are the result of ‘founder effect’ in their respective communities: the Mennonites of Lancaster County, and the Dutch in South Africa. The connection here is that particular portion of the 18th century Dutch population from which the crew of the Zuytdorp, Batavia and Gilt Dragon were recruited came from groups that spawned the Annabaptists, Menonnites or Old Order Amish.

The Marooned

Batavia & Sardam 1629

The first to be marooned were the two recalcitrants – Wouter Loos and Jan Pelgrom de By van Bemel from the Batavia, (which ran onto Morning Reef in the Wallabi Group of the Abrolhos Islands on 4 June 1629). Punishment for their part in the mutiny and murders was abandonment on the WA shore. The location remains a mystery that continues to fuel debate between Phil Playford and Rupert Gerritsen.

7.Slide Hutt River or Witticarra Creek

8.Slide Playford’s Map

Playford claims they were abandoned at Witticarra Creek.

Gerritson, at Broken Anchor Bay – a shallow inlet at the mouth of the Hutt River (450 kilometres north of present day Perth).

Pelsaert notes in his journal that it was the bay he had called at with the long boat while in search of water for shipwreck survivors before heading to Batavia.’[10]

The Sardam also lost 5 sailors that day sent to retrieve a barrel of vinegar floating toward one of the other islands – (a vital ingredient for fighting illness). None were ever seen again. Thus 7 were left behind.

Vergulde Draak 1656

The next ship to go down was the Vergulde Draak in the early hours of 28 April 1656 when it struck a reef five kilometres off the coast, south of what is now known as Ledge Point, 100 kilometres north of Perth. Of the 193 people on board 75, including the Skipper, Pieter Albertszoon, made it to shore. Nothing was saved from the wreck. Survivors subsisted on the few provisions thrown onto the beach by the waves. The Under-Steersman and six sailors were sent to Batavia for help (a distance in excess of 2,500 kilometres) in a long boat. They arrived there on 7 June.[11]

The Governor-General, immediately dispatched the Witte Valk and Goede Hoop to rescue the 68 left behind who were ‘about to go inland where they very much hoped to find provisions and drinking water’.[12]

A mast and campsite found by kangaroo shooters in 1890 are associated with survivors of the Vergulde Draak.[13]

Witte Valk, Goede Hoop (1656)

Of the two ships dispatched to rescue survivors, The Witte Valk returned without landing a shore party because of the wild winter weather.[14]

The Goede Hoop’s shore party proceeded inland for ‘several mijlen’ at the relevant latitude, but did not locate survivors. Instead they lost another three sailors in the dense wattle of the coastal plain.[15]

And the next day, they also lost the crew of eight sent to look for the lost sailors when their longboat boat overturned close to the shore, and was dashed to pieces on the beach.’[16]

The Worsening weather forced the Goede Hoop to sail away, leaving the now 11 sailors to their fate and without having found the original 68. Thus there were now 79 left in WA from the Gilt Dragon disaster.

Waeckende Bouy (1658)

Two years later in 1658, the Waeckende Boey under Captain Volkersen was dispatched to search yet again for the 79 missing on the WA coast. On 26 February he sent ashore a party lead under Upper-Steersman Abraham Leeman. They found ‘a number of pieces of planking placed in a circle with their ends upwards, about 26 kilometres south of the latitude where the wreck of the Vergulde Draak was found in 1963.[17]

On 21 March they found another structure, this time on the beach in the locality of the wreck site. This too comprised planks 8 to 9 feet long [2.4-2.7m] and a foot wide [30cm], that had also been stuck in beach sand with 12 to 13 struts made from similar planking.[18]

Researchers speculate that the first planking circle was erected by the abandoned sailors from the Goede Hoop, using the wreckage of their boat. The second, given its proximity to the wreck, by those stranded from the Vergulde Draak. The Goede Hoop was forced to abandon this search party. Leeman and his crew made for Batavia in a long boat – 4/14 survived.

Zuytdorp 1712

No further boats were reported lost until 1712, (thus 54 yrs Later), when the Zuytdorp ran into cliffs near the Murchison River a few weeks after leaving the Cape of Good Hope on 22 April 1712. The cliffs are highly visible for a considerable distance out to sea during daytime so this must have occurred at night.

Philip Playford’s estimate is that there were at least 200 to 250 people on board. However, until very recently, we could only say with certainty that 156 were on board.[19]In 2009, I came across a journal, among the ‘Heeren Resoluties van de Caap 1712’, in the Nationaal Archief, that noted how the Zuytdorp had waited at the Cape for its 22 sick to return to health and had then also replaced most of the 112, who had died before reaching the Cape, with soldiers from the garrison. This suggest around 290/300 were on board when it left the Cape

Playford (1972), also estimates that between 30 to 180 survived the sinking of the Zuytdorp.[20] His estimate is based on the numbers known to have survived the Batavia and Vergulde Draak shipwrecks. Around 87% of the Batavia managed to survive the initial disaster, even though they were wrecked in the middle of the night, in storms and hundreds of metres from the shore. Nearly 50 per cent of those on the Vergulde Draak also made it to shore. It is presumed that a similar percentage of the Zuytdorp contingent also made it ashore.[21]

Zeewijk

The next ship to founder on the WA coast was the Zeewijk. It went down on Half-Moon Reef in the Pelsaert Group of the Abrolhos Islands on 9 June 1727. Over half the ship’s complement perished. The survivors found refuge on nearby Gun Island. A month later they sent 12 sailors and upper-steersman to Batavia for help in their longboat. Nothing further was ever heard of them. After waiting for months the remaining 88, built a new vessel from the remnants of the Zeewijk, of whom 82 made it to Batavia alive.[22]

The fact that a large number of shipwrecked victims were still alive nearly a year after being marooned increases the possible of that cohabitation took place. Also another 12 may well have ended up on the mainland from the Zeewijk longboat.

Slide 11: Aboriginal map of country

Slide 12: VOC Books

Slide 13: VOC Correspondence

Slide 14: Map of WA not separated from Malaysia

Post Settlement (1829) Indicators)

From the beginning of “British settlement” in 1829, reports about shipwreck survivors started to appear.

On July 5, 1834, the Perth Gazette carried a report that two Aboriginal men, Tonguin and Weewat, had heard of a wreck around 30 days journey, or about 400 miles, to the north. According to the two Aboriginal men, there was ‘white money’ on the wreck[23]

. The following Saturday the Gazette published another version of the same story. In this rendition, the wreck, or ‘broke boat’, as the Aborigines said, also had survivors.[24]

Some months before, other Aborigines from the north had brought some British coins into Perth, claiming that they had received them from indigenous groups to the north.[25]

Investigations of these stories were later conducted by a Swan River Aboriginal man named Weeip and by a party on the ship Monkey, but with no confirmation. It was subsequently determined that the event had actually taken place at least a century earlier[26]

and that the historical chronology had been compressed within the indigenous oral traditions, a common feature of oral transmission.[27]

While these events and speculations were playing out, other stories also began to circulate. In July 1834 some Aborigines reported that they had contact with a party of whites living around 40-50 miles inland of the Swan River.[28]

No more was heard of this group, but in September that year the Perth Gazette re-published a British newspaper report in the Leeds Mercury, of a secret expedition that had revealed an unknown white colony living on the northern shore of New Holland, as Australia was known at the time. These people were said to be of Dutch extraction and to have been the descendants of VOC mariners shipwrecked some generations before. [29]

Others say they came from the Concordia that was lost in 1696.

Over the following decades, these incidents, mixed up with tales of mysterious settler parties and a lost white tribe resident in central Australia, flowed into folklore, eventually developing into a legend complex in which one or probably more, survivors of Dutch shipwrecks settled on the western coast of the continent, intermarried with local Aboriginal groups, and so effectively peopled Australia with Europeans possibly several centuries before the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788.[30]

In later years there would be echoes of these traditions in accounts of a tribe of fair, tall, blonde and blue-eyed Aborigines living to the north of the Swan River. [31]

In 1839 Lt. George Grey and members of an expedition, following a series of mishaps at Shark Bay and Murchison River, while struggling back to Perth on foot, on 4 April when they were just north of Hutt River, according to Grey, they came across yam fields…, ‘as far as we could see’.[32]

He commented that ‘more had been done here to secure a provision from the ground by hard labour than I could believe in the power of ‘uncivilised man’.’[33]

Explorer and surveyor Augustus Gregory later reported that the people from this region, the Nanda, ‘never dug a yam without planting the crown in the same hole’.[34]

When they reached Hutt River on 5 April Grey’s party noted passing the first of ‘two native villages, or, as the men termed them, towns, — the huts … being much larger, more strongly built, and very nicely plastered over the outside with clay, and clods of turf …’.[35]

The first village was in fact only a matter of 200 metres or so from where the fresh water was located by Pelsaert’s crew on the day they abandoned the two mutineers. Recent research estimates that this settlement of permanent dome-shaped dwellings that could accommodate ten people, had an estimated population of 290.[36]

Slide 15: Shipwreck Artifacts found to date

Slide 16: artifacts ie Leyden Tin

Artefact Indicators

Over time a range of objects and artifacts also turned up to provide even more tantalising clues that hint at the survival of marooned. The unexplained uprights and poles from the Vergulde Draak mentioned earlier by Waeckende Bouy search parties were chanced upon again in the mid-19th century at three points along the coast, along with a spectacular “incense urn”, that was handed over to the New Norcia Mission in 1846 by some Juat people who had found it at a well about 20 kilometres south of where the Vergulde Draeck was wrecked.[37]

In 1890 kangaroo shooters stumbled on a mast, ‘about 40ft [12m]’ long, 25 kilometres north of the wreck site. It is presumed to be part of the wreckage of the Gilt Dragon. They significantly also found a large rusty iron pot of about 50 litres capacity, a couple of horn spoons, a copper shovel and two crescent-shaped hatchets all indicating that it may have been one of the survivors’ camp sites.[38]

An extremely weathered, crumbling skeleton was found in 1931 in a small cave, which showed signs of having been occupied at Eagles Nest. A clump of coins was found on the beach opposite the Vergulde Draak wreck site at the same time. Both are presumed to have some relationship to the wreck.[39]

Some Spanish coins and rusty hinges were also found in this locality in 1938.[40]

Another coin was found on the banks of the Moore River, 65 kilometres inland, in 1957. And a single Spanish ducaton, identical to those from the Zuytdorp, was given to a station manager, Charles Gill at Shark Bay in 1869 by an aboriginal man who found it at Woomerangee Hill, 40 kilometres north of the Zuytdorp wreck site.[41]

In 1971 photographer Tony Bell claimed to have found a stone cross laid out on the ground, graves, fragments of green bottles and a ‘roofless stone hut’ to the north of the wreck site,[42]

However, it is difficult to link these with the survivors with any confidence.

An inscribed brass tin, known as a ‘Leyden Tobacco Tin’, similar to those found at other wreck sites, was discovered at Wale Well, 55 kilometres north of the Zuytdorp wreck site in April 1990. It is thought to possibly have come from a survivor of that wreck,[43]

but how it got there is uncertain. An unusual grave at that location, found at the same time as the tobacco tin,[44]

could have some connection, but that too is uncertain.

No other archaeological or observational evidence has yet come to light to provide us with any certainty as to the ultimate fate of any of these marooned seafarers apart from those left by survivors of the Batavia mutiny – the fort structures on West Wallabi and Beacon Islands. And Rock art while compelling is less convincing than the land-based artifacts found at the Zuytdorp wreck site.

Slide 16: Walga Rock and ship

Slide 17: Rock cave art Bigge Island, off the Kimberly Coast.

The whereabouts of the Zuytdorp, began to be revealed in 1927 when material was found on a cliff-face about 60 kilometres north of the Murchison River by stockman Tom Pepper.[45]

However, it was not until 1959 that the identity of the wreck was confirmed by Phillip Playford.[46]

It appeared the Zuytdorp had struck the rocky platform at the base of the Zuytdorp Cliffs (580 km north of Perth), swung side-on and came to rest against the rocky platform, eventually breaking up into three sections.[47]

The discovery also of a considerable amount of material from the wreck on top of the cliffs as well as the slopes would tend to establish that a proportion of the ship’s complement managed to get off the stricken vessel and on to shore. These included cannon breech-blocks and lead sheeting, coins, large bottles, navigational instruments, the remains of chests and barrels, a brass dish, clay pipes, callipers, pins, writing slates, a pistol and musket balls.[48]

The fact that breech blocks and lead sheeting were among the things brought ashore again suggests survivors had time to retrieve non-essential items, since initial efforts after a shipwreck are always directed first to retrieving perishables such as food and water. This is consistent therefore with a scenario of the ship remaining afloat for some time, and this too would have enabled most of the complement to make it to the shore.

Closer to the wreck site researchers also stumbled onto two possibly three campsites and the ashes of a large fire beacon. These indicators also tend to suggest survivors were present in the area for some time after their ship was wrecked.[49]

This is a claim the Nanda and Malgana peoples of that (Kalbarri/Geraldton/Shark Bay) region also make.

Slide 18: DNA Newspaper

NANDA, ORAL TRADITION AND ARCHIVES – LIEU DE MÉMOIRE

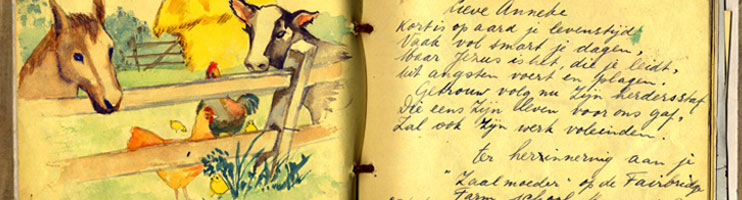

The oral history tradition of the Nanda and Malgana Aboriginals contains references to cohabitation with Dutch mariners. I first came across this notion in 2005, when I met John Mallard, who runs a teaching unit on Aboriginal Health at Curtin University of Technology in Perth, Western Australia. He claimed Dutch heritage and had even been to Holland to connect with his ‘roots’. At our next meeting he brought along a 1941, Western Australian newspaper photograph of his grandfather with the Zuytdorp figurehead, which had become an important part of his family’s history – a lieu de mémoire of cohabitation. The existence of many light-skinned, with blue eyes and fair hair, Aborigines in Nanda folklore and the belief that there is some truth to the legends is the basis upon which the National Library conducted interviews with Nanda for their collection.

Slide 19: Genealogy showing Ellis van Creveld

During his growing years his family were still practicing many of the old ways. “My father and my mother were introduced as a formal part of Aboriginal marriage. In this case four brothers were taken across and met four sisters. My father and his younger brother were successfully matched with my mother and her sister and the two other brothers and two sisters weren’t a successful match, so the brothers were taken across to Mullewa later and met two sisters from another family and that was a successful match. So you had two lots of brothers marrying two lots of sisters.

John acquired his information about cohabitation from his grandfather, “… I was a very inquisitive child and always asked questions and I got that information via him, but I also got information about this from my mother, who is from the Wadjarri. She tells a story about white fellas, going way back, that was walking up one of the rivers through where Mullewa is now….” Pastoral settlement took place in the region between Shark Bay and the Murchison, but although traditional society no longer existed by the 1920s, the oral traditions about cohabitation among the Nanda persist into the present.

Collective identity is based on the elective processes of memory, so that a given group recognises itself through its memory of a common past.

[50]

That common past, sustained through time into the present, is what gives continuity, cohesion and coherence to a community. To be a community, a family, a religious or ethnic community involves an embeddedness in its past and, consequently, in the memory texts through which that past is mediated.

In this instance is supported by genealogical information that links the Councillor and Mallard families via Sarah Feast, who first married Charles Mallard and after his death Barrowa (John Oona Councillor). These families also record Ellis van Creveld syndrome.

The other Aboriginal group who may share a common past with the Dutch are the Noongars. Nyungars live in the south-west corner of Western Australia. The Vergulde Draak, whose 68 survivors were never found, was wrecked on the coast of Noongar country. Their country butts onto that of the Nanda.

A further clue that it may have taken place comes from an 1833 article in the Perth Gazette newspaper that mentions the Aboriginal man Yagan, “a subject of terror to the white people, who yet commanded their admiration” was seen in Perth with his two sons, estimated to be around 9 and 11 who, the journalist notes answer to the names Narli and ‘Willem’. The journalist who estimated Yagan’s height to be over 1.8 metres tall, also described him as ‘having a greater stature than the average aboriginal, “head and shoulders above his fellows – in mind as well as in body”. More compelling even than these physical indicators are medical research.

Several other reports over many years (1830s to 1945) attest to some aborigines in the region having fair skin and European facial features. Others talk of albinos. For example, between 1890 and 1945, newspapers around Australia at various times carried articles about an albino Aborigine from the La Grange area near Broome called Jungan or Jan Gun. An article in 1934 recounts recollections of 40 years earlier by Miss K. McPhee, the sister of Mr Alex McPhee, the owner of La Grange Pastoral Station, who she claimed her father had ‘discovered’ Jan Gun (Jungun). She also mentioned she owned an enlarged photo of Jan Gun that had a lock of his reddish brown hair attached to it.

[51]

The newspaper journalist who wrote the article speculates that Jan Gun (Jungun) could be the offspring of the lost explorer Leichardt. It appears that Jan Gun was considered so exotic in fact that he was displayed at numerous venues around Australia including the Victorian Waxworks Museum.

Folkloric tradition of the times also reported group of Albinos as purportedly seen on the plains behind Hall’s Creek and Wave Hill. On Saturday 3 February 1890, the West Australian Newspaper ran an article by E.H. on Pieter Ngarras, an aboriginal who displayed European features”. It notes:

“With a great blonde beard, not white but bright golden, sturdy sinuous limbs decidedly bandy, a noble, girth and a passion for the. sea— none of these aboriginal characteristics; Provided that there is the same ‘strong..- atavistic tendency among, white races as there are among the negroid and Asiatic, Pieter is quite possibly, an amazing throw-back over 14 or 15 generations to the early Dutchmen, it may be to the two desperadoes marooned by Pelsart near Champion Bay in ‘1627. The supposition is not an absurdity in that Mendel himself allows the passing of 17 generations for the verification of his theories. Residents of Shark Bay have assured mie that Pieter’s forebears were all typical aborigines, and his ancient sister Mithie, the only, other full-blood that now exists there, is unremarkable. With a hollow nose and black skin incongruous with his white characteristics, this man spends his life cruising the shallow waters of Hamelin Pool, where he is well known as a ‘hard case’ of the stations. His most cherished possession is a little dinghy which he has fitted with a mast and’ sail, and in which and on which he is eternally working— a trait in itself most unaboriginal, harking right back to the Eendracht, the Vergulde Draecke.and other adventurers who scoured those seas in the dawn of our history, with many crews marooned and shipwrecked there.

Among the most prominent genetic indicators upon which journalists speculated that cohabitation with Europeans had possibly occurred before colonisation by Britain – were tallness and baldness. This firstly based on the observation that northern Europeans are relatively tall and the impression,[52]

drawing on very limited evidence, that the Aboriginal people from the upper Murchison and Gascoyne Rivers, and from Shark Bay to the north west coast, were also relatively tall, the latter populations particularly.[53]

Baldness appears to have been uncommon in all Aboriginal populations except along the Murray River in south-eastern Australia.[54]

However, anecdotal evidence indicates it was a feature in the central west of Western Australia, from the coast to the western edge of the Western Desert.[55]

Surveyor Phillip Chauncy commented that in the 1840s and 1850s the “only bald natives I ever saw were the warran [yam] diggers [of the central west coast region].

The most dramatic, albeit unverified, claim of unusual physical attributes of Aboriginal populations from the cental west of Western Australia arose in 1861 when the Perth Gazette reported:

“From Champion Bay [Geraldton] we hear that a tribe of natives have made their appearance at the eastern most sheep stations upon the north branch of the Upper Irwin [River[56]

], who differ essentially from the aborigines previously known, in being fair complexioned with long light coloured hair flowing down to their shoulders, fine robust figures and handsome features: their arms are spears … which they throw underhanded.”[57]

Diseases associated with Cohabitation

Porphyria Variegata and Ellis van Creveld are two syndromes that have been associated with cohabitation. These syndromes are the result of founder effect in the their respective communities the Mennonites of Lancaster County, USA and the South African population. In population genetics, the founder effect is the loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population in isolated human populations such as the Amish and Aborigines.[58]

Biodiversity is often used as a measure of the health of biological systems….from effectively zero. Considered a lead for some time was information from an American woman who had married an Aborigine from the Shark Bay region. She informed researchers her husband died from a rare metabolic disease called porphyria variegata. This appears to genetically link Aborigines from the area to Afrikaner progenitors of the diseases. The Zuytdorp is known to have arrived at the Cape in March 1712, where it took on extra crew. It is thought a son of the progenitors may have been among them.

The genealogical studies of Dean and Barnes suggested that the gene for the South African form of variegate porphyria was introduced into South Africa in 1688, when two Dutch settlers, Gerrit Jansz van Deventer and Adriaantje Ariens married in Cape Town. This has now been proven: most South African patients carry a single founder mutation, and haplotype analysis of the ancestral chromosomes has confirmed a relationship with Dutch families with variegate porphyria. In the years following 1688 the gene spread widely through South African populations and is common amongst South Africans of Dutch ancestry, whatever their race or home language.[59]

In 2002, researchers from the Biochemistry Section of QEII in Perth together in collaboration with researchers from the Department of Genetics University of Stellenbosch analysed 296 cases of pophyria in WA between 1978 and 1998, that included three Aborigines. They concluded that the mutations causing variegate porphyria in the Western Australian Aboriginal population occur sporadically and were not inherited from shipwrecked sailors. (Intern Med J 2002; 32: 445−450).[60]

Ellis van Creveld

Another rare genetic feature among the Nanda is Ellis van Creveld syndrome (chondroectodermal dysplasia). The many symptoms that characterise this autosomal recessive syndrome include highly visual polydactylism, the growth of extra fingers and toes. The syndrome has increased incidence among persons of Old Order Amish of Pennsylvania descent, especially those from Lancaster county.[61]

In the general population of the United States, the frequency is 1 case per 60,000 live births, whereas among persons of the Old Order Amish, the incidence is estimated at 5 cases per 1000 live births. The frequency of carriers in this population may be as high as 13 per cent. [62]

Goldblatt et al documented the second highest incidence of Ellis van Creveld to be among the Aboriginal population in the south-west of Western Australia who have a purported carrier prevalence of 1/39 live births.

Goldblatt et al implied the syndrome was introduced by Dutch seafarers.[63]

Goldblatt et al reported on two children with Ellis-van Creveld syndrome in the Mallard (Nanda) extended kindred of Western Australian Aboriginal descent. A further two family members with isolated postaxial polydactyly of the feet (as probable heterozygous manifestations of the Ellis-van Creveld gene). These male and female second cousins both had short limbs, postaxial polydactyly and cardiac malformations. Goldblatt et al, proposed that founder effect and random genetic drift resulted in a relatively high frequency of the Ellis-van Creveld gene in the Aboriginal people of Western Australia. The apical ancestor of these families is a Nanda woman Alice McMurray who was married first to Charles Mallard Jnr and later to John Councillor of the Naaguja Peoples of the Hutt River area. They are also related to the Drage family in Carnarvon.

The progenitors among the Amish in Lancaster county are Samuel King descended from an Anabaptist family of Steffisburg, Bern, known as Köng or Küng (in Bernese dialect, equivalent of German Alsace König also spelled Koenig).

They had five daughters and two sons, Hans (b. 1684) and Samuel (b. 1689), either of whom could have been the father of Samuel König/King (b. c 1724). Samuel Köng was an Anabaptist. In December 1744, Samuel and his brothers Jacob and Christian migrated to Philadelphia. In 1750 Samuel married Anna Yoder (b. 1728 in Europe) in Berks county. He died on Jan 16 1777, he and his wife having produced 12 or possibly 14 children. It is thought that about 12% of the Amish Mennonite population of Lancaster County have the surname King and are the descendants of Samuel and Anna.

The Old Order Amish derive from the Dutch Mennonite sect of the Anabaptist groups formed in Switzerland and elsewhere during the Reformation, whose members began migrating to the USA in 1683 to escape persecution in Europe. It is hypothesized that if a common genetic link between both the Amish and Aboriginal populations can be established it is highly likely that Europeans, probably Netherlanders, introduced it.

In any case there were significant Dutch Mennonite populations throughout the Netherlands at the time and in particular a large one at Franeker, which is located opposite Texel on the mainland.

Germans in the VOC

Highly acclaimed journalist, Roelof van Gelder notes that of the nearly one million people in service to the VOC in Asia between 1602-1795, globally fifty per cent were foreigner (to the Netherlands). Of these Germans comprised by far the largest number.[64]

VOC crews contained numerous Germans looking to make good in the booming Netherlands Golden Age economy. On arrival many were told a stint on a VOC ship would set them up financially. The composition of the Zuytdorp crew reflects van Gelder’s thesis. However, of the 286 on board when the ships left the Netherlands, 112 died enroute to the Cape, another 22 were sick on arrival. The Zuytdorp waited at the Cape for the 22 to be nursed back to health and also recruited the number lost enroute from the local garrison. However, there are no records as to who they were. Hence we are working very much in the dark.

Slide 20: Ethnic composition of soldiers on board Zuytdorp

Ethnic Composition of the Zuytdorp

Soldiers Shipping List 1711/12

| Soldiers and trades persons | Nos. |

| Netherlands | 34 |

| Germany | 35 |

| Switzerland | 04 |

| Norway | 03 |

| Prussia | 04 |

| Belgium | 07 |

| Denmark | 01 |

| Latvia | 01 |

| Difficult to decipher | 15 |

| Total | 104 |

Monsterrol, uitgande reis Zuytdorp,1712

VOC Archives The Hague.

Slide 21: Cartoon traded genes?

Geneticists

The genetics researchers will use Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA markers to determine the ancestral composition of each population and determine the level of relatedness between them. Recent discovery of the E-vC gene, its mutations and mitochondria should lead to a better understanding of the probabilities that EvC is linked to cohabitation![65]

The results of these activities will be collated to demonstrate conclusively that the traditional stories of the Nanda and other relevant narrative traditions regarding their Dutch ancestry are accurate or not. The various genetic data collected will be analysed under the supervision of Dr Jack Goldblatt et al at Princess Margaret Hospital and Dr Vanessa Hayes of the Sydney Children’s cancer laboratories.[66]

Barry Marshall group.

CONCLUSION

The current project is to analyse existing research from the various disciplines together with new archival and genetic research, resulting, we hope, in a synthesis that will produce a conclusion regarding the Nanda oral history tradition that Dutch mariners cohabited with them.

A positive outcome would have ramifications in Australia, the Netherlands, Britain and the United States. Most particularly it will be of profound importance to the Nanda people themselves, providing them with conformation, or not, of their long-held beliefs about this aspect of their ancestry as it relates to their native title claim. If pre-1788 European settlement is confirmed, this will also help with the development of a much-needed indigenous heritage tourism industry in the region, with consequent economic and social benefits.

[1] This money format was plagiarized[citation needed] in other countries and the word florin is used, for example, in relation to the Dutch guilder (abbreviated to Fl).

[2] Ibid, p.41.

[3] Traditionally, all partners were subject to unlimited liability of the company’s obligations. However, the VOC differed in that it was the company that was liable and not its partners. Instead, the liability of the partners was limited to the amount they agreed to pay for shares. In this way the shift from unlimited to limited liability further reduced the risk to the non-managing partners. In fact the role of VOC participants would now be called investors. Moreover, the shares they were issued became tradable at the Amsterdam stock exchange, which was probably the first of its kind in the world.

[4] The large establishments, where the VOC exercised a territorial authority, were under the authority of a gouverneur (governor). About 1685 these were Ambon, Banda, the Moluccas (Ternate), Coromandel, Ceylon and Malacca;A directeur (director, a title which, in the Company parlance, was associated with trade) headed the Cape of Good Hope, the north coast of Java and Makassar. Bengal, Surat and Persia were headed by a Malabar and on the west coast of Sumatra (Padang) a commandeur (commander). Cheribon, Banjarmasin and Palembang a resident, and Japan and Timor an opperhoofd (head of establishment).

[5] In 1795, the Cape was occupied by the British when the Netherlands were occupied by revolutionary France, so that the French revolutionaries could not take possession of the Cape with its important strategic location. An improving situation in the Netherlands (the Peace of Amiens) allowed the British to hand back the colony to the Batavian Republic in 1803, but by 1806 resurgent French control in the Netherlands led to another British occupation to prevent Napoleon using the Cape. The Cape Colony subsequently remained in the British Empire, becoming self-governing in 1872, and united with three other colonies to form the Union of South Africa in 1910.

[6] Geoff Wharton, The Pennefather River: Place of Australian national heritage, Gulf of Carpentaria Scientific Study Report, 2005.

[7] R.T. Appleyard & T. Manford. In the Beginning, UWA Press 1979.

[8] Gerritsen notes that official documents record 73 individuals from these ships as last seen alive on the shores of the coast of Western Australia between 1629 and 1656.

[8] And a further 25, between 1629 and 1727, who disappeared near the shore or in close proximity to the coast from landing parties sent to rescue them. The table of shipwrecked and marooned survivors shows some were rescued, many were not.

[9] http://www.nederland-australie2006.nl/geschiedenis/nl/html/ontdekkingsre…

[11]

‘Resolution of the Council for the Indies, 7 June 1656. Algemeen Rijksarchief, Kolonial Archief VOC (ARKA-VOC) 577’, in J Green, The loss of the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie jacht ‘Vergulde Draeck’, Western Australia 1656, 2 vols, British Archaeological Reports. BAR Supplementary Series 36(i), Oxford, 1977, vol.1, p. 48.

[12]

‘Letter from Governor-General and Council to the Council (Chamber of Amsterdam) of the VOC, 4 December 1656. ARKA-VOC 1214 fol. 84r’, in J Henderson, Marooned, St George Books, Perth, 1985, p. 54.

[13]

WAD Researchers speculate that some of the 118 left on the Vergulde Draak possibly made it ashore clinging to wreckage, swimming or floating. But that currents would have carried them to other parts of the coast, away from where the main body of survivors had assembled.

[14]

‘Letter …. 4 December 1656’, in Henderson, 1985, p. 54.

[15]

‘Report by Governor-General to Heeren XVII, 4 December 1656 (Letters and papers sent over in 1657). ARKA-VOC 1104.’

[16]

‘Report from Governor-General to Council of the VOC, 28 November 1656. ARKA-VOC 1104 fol. 3-4’, in Green, 1977, vol. 1. p. 50; ‘Sailing Orders for ‘Emeloordt’ and ‘Waeckende Boey’ 31 December 1657’, in Henderson, 1985, p. 62.

[17]

See R Gerritsen, And their ghosts may be heard, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, South Fremantle 1994, pp. 42-3, 291 for discussion on the location of this and the second structure; Day Register by Samuel Volkersen of Waeckende Boey — 26 February 1658’, in Henderson, 1985, p. 96.

[18]

‘Journal or daily register of Abraham Leeman’, 21 March 1658, Battye Library MS PR 3756/1.

[19]

PE Playford, ‘Wreck of the Zuytdorp on the Western Australian coast in 1712’, Journal and Proceedings of the Western Australian Historical Society vol. 5(5), 1959, p. 36; PE Playford, Carpet of silver: the wreck of the Zuytdorp, University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands, 1996, pp. 61, 200.

[20]

Gerritsen, 1994, pp. 37-8 (40-180 survivors); Playford, 1996, pp. 203 (30 survivors).

[21]

Gerritsen 2009, forthcoming

[22]

Letter of Governor General Council 31 October 1728 cited in Henderson Unfinished Voyages (1980 edition) p.47; Edwards 1971:86-168; Ingelman-Sundberg 1978:7-10; Gerritsen 1994a:38-9.

[23]

Perth Gazette July 5 1834, p. 314

[24]

Perth Gazette July 12, 1834 p. 318

[25]

Perth Gazette July 19, 1834 pp. 322-333

[26]

Thought to be the wreck of the VOC ship Zuytdorp in 1712, though the wreck of the VOC Vergulde Draeck off Ledge Point in 1656 also left survivors whose ultimate fate is unknown.

[27]

See for example, Vansina, J., Oral Tradition: A Study in Historical Methodology. Chicago and London: Aldine and Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1961 and his Oral Tradition as History, James Curry, 1985.

[28]

Perth Gazette July 26 1834, p. 326.

[29]

Perth Gazette September 20 1834, p. 359

[30]

Rupert Gerritsen, ‘The evidence for cohabitation between Indigenous Australians, marooned Dutch mariners and VOC passengers’, in Nonja Peters (ed.), The Dutch down under, 1606-2006, University of Western Australia Press, Crawley 2006) 38-55.

[31]

Gregory A C, Inaugural Address, Proceedings of the Queensland Branch of the geographical Society of Australasia, 1, pp. 18-25. See also Gregory, Augustus Charles, Journals of Australian explorations, .Adelaide : Libraries Board of South Australia, 1969 (1884). Daisy Bates wrote of her encounters with Aboriginal people with ‘Dutch’ features, Bates, D., My Natives and I, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park WA, 2004, p. 118.

[32]

G Grey, A journal of two expedition in north-west and western Australia during the years 1837-39, vol. 2, T. & W Boone, London, 1841, p. 12.

This was the first of numerous yam fields that existed at the time of British colonisation in the river valleys of the Geraldton region.

[33]

Grey, 1841, p.12.

[34]

AC Gregory, ‘Memorandum on the Aborigines of Australia’ in H L Roth,’ On the Origin of Agriculture’, Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 16, 1887, p. 131.

Gregory had in fact reported this first the previous year.

[35]

Grey, 1841, p. 19.

[36]

R Gerritsen, Nhanda villages of the Victoria District, Western Australia,Intellectual Property Publications, Canberra, 2002.

[37]

Gerritsen, 1994, pp. 49-50; A curious ‘Circle of Stones’, 5-6 metres in diameter with one or two of radiating lines, first seen in 1875 in very inaccessible country 200 kilometres north of the Vergulde Draeck wreck site, is also thought to have possibly been constructed by the survivors from that ship.

[37]

The Indigenous population in the area, the Juat, do not appear to have traditionally constructed stone arrangements, and it is unlike any other stone arrangement in southern Western Australia. The location itself, unlike most other ceremonial sites, is quite inhospitable. It is thought that perhaps the structure was created to indicate that the survivors had been there and the direction in which they intended to proceed.

[38]

ibid., p. 52.

[39]

ibid., p. 53-4.

[40]

ibid., p. 53.

[41]

Inquirer and Commercial News, 12 May 1869, p. 12; Playford, 1959, p. 38-9.

[42]

The Sunday Times, 23 May 1971, p. 4. But see Henderson, 2007, p. 48.

[43]

Playford, 1996, pp. 214-6.

[44]

The West Australian, 8 September 1990, p. 6.

[45]

There has been considerable debate about who first found the wreck in modern times. although he may have actually been directed there by members of the Drage family See Playford, 1996, pp. 82-100; G Henderson, Unfinished voyages: Western Australian shipwrecks 1622 – 1850, University of Western Australia Press, Crawley, 2007, pp. 47-8.

[46]

Playford, 1959.

[47]

Playford, 1996, pp. 115, 201-3.

[48]

Playford 1960:24-29; Gerritsen 1994a:36-7; Playford 1996:82-4,120-27.

[49]

Playford 1996:120-24.

[50]

Michael Piggott, “Archives and memory”, in: Sue McKemmish, Michael Piggott, Barbara Reed and Frank Upward (eds.), Archives: Recordkeeping in Society (Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga 2005) 299-328.

[51]

The Queensland Observer, 22 October, 1898; Argus West Australian,

[52]

No specific study was done of height in traditional Aboriginal societies in Western Australia so this argument relies upon fragmentary records and observations.

[53]

Gerritsen 1994a:76-7.

[54]

Birdsell 1972:506.

[55]

Gerritsen 1994a:75-6.

[56]

Approximately 100 km east of Geraldton.

[57]

Perth Gazette 9 August 1861, p.2.

[58]

It was first fully outlined by Ernst Mayr in 1952, using existing theoretical work by those such as Sewell Wright.Sewall Green Wright (December 21, 1889 – March 3, 1988) was an American geneticist known for his influential work on evolutionary theory and also for his work on path analysis. With R. A. Fisher and J.B.S. Haldane, he was a founder of theoretical population genetics. He is the discoverer of the inbreeding coefficient and of methods of computing it in pedigrees. He extended this work to populations, computing the amount of inbreeding of members of populations as a result of random genetic drift.

[59]

University of Cape Town website – www.pophyria.uct.ac.za/professional/prof-vp…).

[60]

- Rossi, C. Y. B. Chin , J. P. Beilby , H. F. J. Waso and L. Warnich, ‘Variegate porphyria in Western Australian Aboriginal patients’ Biochemistry Section, Pathcentre, QE II Medical Centre, Nedlands, Western Australia, Australia and Department of Genetics, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118962878/abstract?CRETRY=1&S…

[61]

Ellis van Creveld syndrome, also known as ‘chondroectodermal dysplasia’, is a rare genetic disorder characterized by short-limb dwarfism, polydactyly (additional fingers or toes), malformation of the bones of the wrist, dystrophy of the fingernails, partial hare-lip, cardiac malformation and often prenatal eruption of the teeth…

[62]

McKusick, Victor A ‘Ellis-van Creveld syndrome and the Amish’, Nature Genetics 24, 203 – 204 (2000) ; www.emedicine.com/ped/topic660.htm).

[63]

Goldblatt, JC Minutillo, PJ and J Hurst.1992. Ellis-van Creveld syndrome in a Western Australian Aboriginal community, Postaxial polydactyly as heterogenous manifestation, Medical Journal of Australia, 157: 271-272.

[64]

Roelof van Gelder, Het Oost Indisch avontuur:Duitsers in dienst van de VOC, Sun; Nijmegen, 1996.

[65]

Chen & Laufer-Cahana 2006.

[66]

Twelve y-chromosome markers (six single nucleotide polymorphism markers and six short tandem repeats

[66]

will be analysed in male samples with genotypes determined using restriction site polymorphisms.

[66]

Haplotypes will be defined according to the evolutionary relationships of the markers and the standard Y chromosome consortium mutation based nomenclature (Y chromosome consortium 2002). To identify complementary female origins and diversity, the mtDNA hypervariable sequence 1 (HVS-1) will be amplified using primers L15996 and H16401

[66]

with M13 (121) and M13 reverse sequence primers attached to the 5’-end of each primer respectively. HSV-1 haplotype diversity will be determined according to Nei

[66]

with the average number of nucleotide submissions per site between pairs of sequences calculated using the model by Tamura and Nei

[66]

. The samples also will be screened for the mtDNA 9-bp deletion, which is located in the COII/tRNALys intergenic region.