Post-war Dutch and other migration to Australia 1945 – 1970

Presentation by: Dr Nonja Peters

Date: 28 September – 2 October 2011

Danish Emigration Archives and Utzon Center

Aalborg, Denmark.

Migration History Matters

Association of European Migration Institutions (AEMI)

Annual Meeting and Conference

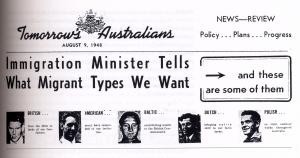

This presentation looks at how local, national and global influences and social, cultural and economic policies of the day in the Netherlands and Australia shaped the expectations of the 160,000 first and second-generation Dutch immigrants recruited by Australia post-WWII 1951-1961. I show how the impressions of Australia and Australians harboured by most Dutch emigrants were derived from a government that wanted to get rid of them, a government that was desperate for their labour power and a migration propaganda machine prone to sensationalising.

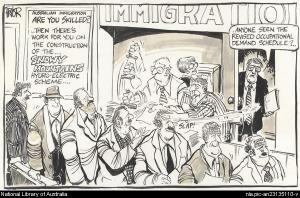

Post-war Immigration 1945- 1970

Postwar, Australia sought immigrants to specifically increase the population and overturn the flagging birth rate, for reasons of defence and to fill employment vacancies in the skilled trades and semi- and un-skilled labour areas in heavy industry, the burgeoning building and construction sectors and public utilities. The target was 2 per cent increase per annum with half of that provided by immigration, which in numerical terms was a target of 70,000 newcomers.

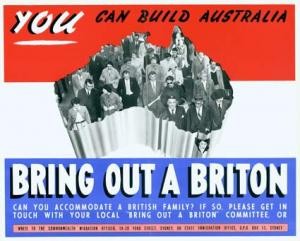

Wanted: Britons?

Wanted: Britons?

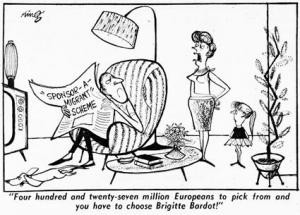

However, when the Commonwealth Government could not acquire enough Britons to emigrate, due to Britain’s post-war reconstruction plans and a major shipping shortage, following the recruitment of 180,000 Displaced Persons, via the IRO, in 1951 they were quick to invite the racially (physiognomically) similar, blonde, blue-eyed, Dutch families, and confer surrogate British status on them. Agreements with Italy and Germany followed.

Recruiting Europeans but who? European ‘Good Types’

The European Influx!

The European Influx!

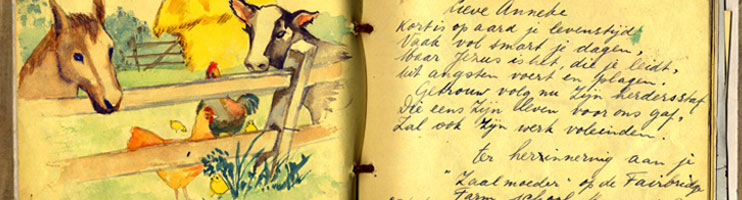

Leaving the Netherlands

Large Dutch Families wanted!

Compared to other ethnic groups, Dutch migration was overwhelmingly family oriented. Women generally accompanied their men folk, not always out of choice but because it was considered their duty to go wherever their husbands chose to earn a living. Australia, chose Dutch for their workplace skills and behaviours and the large families they tended to have. As these would provide the workforce with future participants and because large families were less likely to leave given the costs involved. This proved to be a workable arrangement because Dutch Calvinist and Catholics – the two religions that rejected birth control both encouraged emigration.[3] Their clergy insured migration’s success by charging Dutch wives with the custodianship of their husband’s and children’s spiritual welfare and with creating a gezellige (convivial) home in Australia, wherever the family had to live.[4]

Overpopulation Concerns? Dutch Overpopulation

The postwar diaspora out of the Netherlands was out of other Western European countries, was greatly motivated by ‘overpopulation concerns’. Resurrected by various governments to rid themselves of ‘surplus people’ from depleted economy’s experiencing massive un/under-employment and serious housing shortages. For example the Dutch Monarchy and Government constantly exerted pressure on Dutch citizens to register for emigration at one of the many offices set up around the country specifically to promote their exodus.[5] Dutch were recruited by Australia for their skills in the trades skills and semi-skilled operatives for the burgeoning building and construction and manufacturing industries and less frequently as unskilled labour.

Prospective emigrants were lured to Australia at information evenings organised at these centres where Commonwealth Department of Information propaganda was also vigorously promoted.

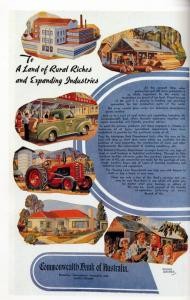

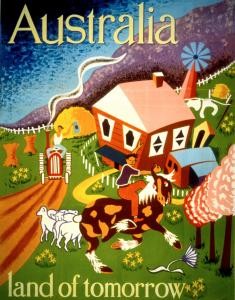

Oz invites you

Oz invites you

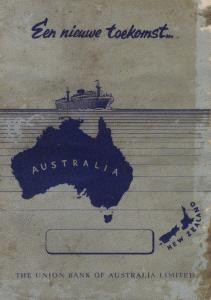

New Future!

New Future!

Designed to attract foreigners to go the extra distance to Australia the placards, fliers and brochures depicted Australia as the future – a country with booming industry, full employment, boundless opportunities and good working conditions, where an immigrant could own their own motor vehicle and a home of their own filled with countless whitegoods and assistance to integrate. This level of materialism was unheard of in post-war Netherlands. Moreover, it could be reached with passage assistance, to which both governments contributed! All that was required of a potential emigrant was that they meet race – the White Australia policy governed entry requirements – age and health criteria and remain in the type of employment for which they were selected by Australian authorities for two years.[6](Note: bilateral agreements differed e.g. DPs were recruited as ‘domestics and labourers’ whatever their education qualifications). This did not extend to Dutch from the Netherlands Eeast Indies unless they could prove they were 51% White![7]

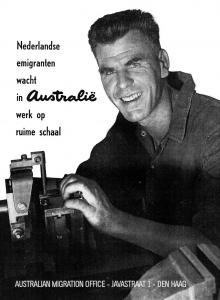

Nederlandse emigranten wacht in Australia werk op ruime schaal – Australian Migration Office

Work on grand scale

Work on grand scale

A reporter from ‘De Waarheid’ [The Truth]. who attended one of many information evenings held by the local Labour Office in Amsterdam, noted the disparity between the image Dutch gained at these events, of Australia and Australians, before leaving the Netherlands from the possible reality of their experience post-disembarkation. In an article on 28 January 1950, he writes:

“It was the twenty-third evening, and the small room was full to overflowing. The 500 people present were seated not only on the seats but also on the window

ledges, the stairs, and on tables. Hundreds succeeded in obtaining standing room only. At these meetings people are told, among other things, how large

Australia is and how small Holland is. It is also said our country is too densely populated. Many of the audience, already determined to emigrate visualise the

Australian landscape; extensive wide fields, steppes carrying millions of sheep, mountains, primeval forests, and extensive industrial centres; skies are blue,

clouds are white, the mountains are purple, and the fields green – just as on the poster. The more the listener hears about this land the more he is lured on by

visions of wide-open spaces. Each of the un-or underemployed in the room hopes to be among those to leave for the vision.”[8]

However, ‘De Waarheid’ also noted ‘in the course of the evening, that while emigrants were told the requirements for entry to the ‘great promised land’ would entail a struggle with an avalanche of paperwork that debate never got beyond a ‘very basic level’. He attributed this to people being too shy to speak up in public. And that this gave the propagandists the chance to sum up the discussion on an enlightened and positive note.[9] He saw as very problematic the lack of consideration given to the emotional complexity of migration. To confront a new language and an entirely different culture. How hard it would be to say goodbye, to leave everything behind to start a new life in a strange land far from home, kin and friends forever!

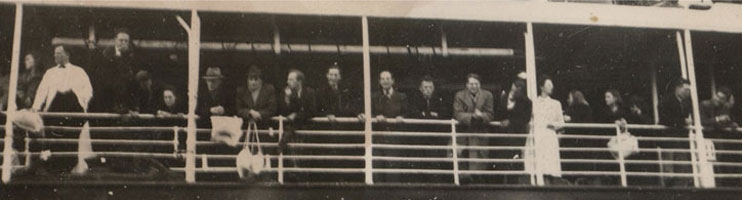

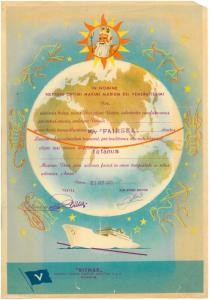

Migrants’ impressions were formulated further by experiences and discussions on the journey over, which in the 1950s was mainly by sea.

The Good Trip

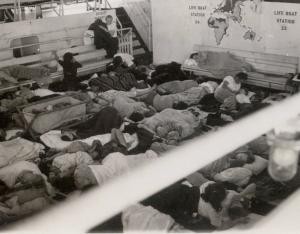

The Bad Trip – Troop ship accomodation

Migrant Camps

On arrival in Australia a building material shortage forced especially the larger assisted families to start their life in Australia at one of the Department of Immigration accommodation centres in rural or metropolitan WA. Military camps were used because they could be refurbished with minimal recourse to the seriously depleted labour and building materials resources.[10]

The primitive conditions at camps was most difficult to confront by Dutch women travelling on P&O or Nedlloyd luxury liners such as the MS Himalaya and MS Johan van Oldenbarneveldt. They describe feeling especially overwhelmed by the transition from a well appointed cabin to a bare cubicle at a Department of Immigration accommodation facility in which barracks had been converted into ‘louse-infected little cubicles’, which offered but a semblance of privacy since the partitions were only man-high, so you shared noises, sounds and smells with everyone else in the barrack!’ A Dutch girl recalls the culture shock of arrival at Bonegilla where the largest Dutch contingent were accommodated as:

The primitive conditions at camps was most difficult to confront by Dutch women travelling on P&O or Nedlloyd luxury liners such as the MS Himalaya and MS Johan van Oldenbarneveldt. They describe feeling especially overwhelmed by the transition from a well appointed cabin to a bare cubicle at a Department of Immigration accommodation facility in which barracks had been converted into ‘louse-infected little cubicles’, which offered but a semblance of privacy since the partitions were only man-high, so you shared noises, sounds and smells with everyone else in the barrack!’ A Dutch girl recalls the culture shock of arrival at Bonegilla where the largest Dutch contingent were accommodated as:

“From living in a three storey house in The Hague, a city of distinction, to unlined army barracks

where walls were of Hessian to separate families, the beds were hard with grey blue-striped cheap

blankets. Privacy was non-existent as conversations could be heard from one end of the army hut

to the other.”[11]

The Dutch and Australian governments kept pushing the idea that the ‘right type’ of migrant would make it in Australia despite the challenges of resettlement; and translated that meant ‘persons willing to put in the hard yards’.

A mass protests about conditions occasioned a visit to Bonegilla camp by Dr Pieters cultural attaché to the Dutch embassy, who (famously) advised: “See those hills around us? At first the climb will be difficult but, once you get to the top and see the other side, you will be so happy”![12] The notion of having failed at migration – and there was little sympathy for migrants who returned to the Netherlands – was also a strong driving force.

A mass protests about conditions occasioned a visit to Bonegilla camp by Dr Pieters cultural attaché to the Dutch embassy, who (famously) advised: “See those hills around us? At first the climb will be difficult but, once you get to the top and see the other side, you will be so happy”![12] The notion of having failed at migration – and there was little sympathy for migrants who returned to the Netherlands – was also a strong driving force.

The many complaints about the reality compared to propaganda prompted the then Minister for Immigration Harold Holt, to instruct his staff at the Department of Information to paint a ‘grimmer picture’ in propaganda booklets about Australia than had been the case in 1950, because it was giving people the wrong impression.[13]

After this debacle the Dutch government did also began to employ ‘Escort Officers’ on board Dutch ships to handle further enquiries. Mr H.P. Francissen on the Grote Beer noted:

“In my candid opinion the information these people receive in Holland is far from satisfactory. They are entirely without practical knowledge about the country

in which they hope to make a new start in life.”[14]

Leaving the camp was problematic, many families resorted to living in dilapidated rentals, old tram carriages, ‘tents, garages, caravans or verandas until the family could afford the deposit on a second-hand house or a block of land. ‘Strapped for cash’ the whole family was expected to contribute their earnings or time, or both, on weekends and after work or school, cleaning old bricks or making their own from the meagre weekly allocation of cement that the building material shortage allowed. When they had sufficient to erect a one-car garage or the back veranda of their future home these Dutch were forced to come up with innovative ways to cram their many children into the smallest spaces.

From the old to the new – From crowded Europe to Australia’s wide open spaces!

From Migrant camp to building your own home 1949 – 1970

Birss Family Residences, Albany, Western Australia 1952

By this time the myth of finding ‘gold nuggets lying on the streets’ had been dispelled. Migrants were coming to terms with the harsh reality that they would have to work at assimilating and that nothing but hard toil would buy them the quality of life and the material possessions they dreamed of. If only because subsidized Dutch immigrants had been forced to give up everything they had towards their passage costs. This meant many had arrived virtually destitute, with only landing money (which in 1950 was £10 for singles and £20 for a family) and a packing crate of household possessions measuring no more than one cubic metre. These criteria also left most Dutch without the collateral they would need to access bank loans or other affordable financial support.[15] The imperative to assimilate caused additional stress.

Assimilation

The focus on assimilation or ‘Anglo conformity’ by this ninety per cent Australian-born and English speaking society and the demand that newcomers assimilate quickly and totally to its culture not only implicitly asserted the superiority of Australian culture over theirs it also guaranteed that Australia’s essential Britishness would remain. Australians expected that the ‘New Australians’ would become so completely absorbed, in fact, that it would be as if they had never come at all![16] The expectation to assimilate was commented on in the Dutch Catholic newspaper De Tijd. On 1 September 1950 it noted:

“Only for the man and woman who have given up all ideals of a Dutch home life, and are capable of putting themselves on the level of the average Australian, is there a chance of success. The authorities in Holland should warn migrants that on arrival in Australia they have no rights but only responsibilities to become ‘New Australians’ in the shortest possible time.”[17]

Orientation & Language Acquisition – learn both languages !

The Dutch Response to the Assimilation Imperative

Aanpassen (to adjust to) was how the Dutch responded to the Australian imperative. Aanpassen, or Dutch assimilation ideology and practices, are distinctive because, throughout the assimilation period, whether they considered them agreeable or not, the majority of Dutch appeared willing to conform to them – at least in the public sphere. Generally in public settings the Dutch appeared to want to get rid of or at least cover-up any social characteristics defined as ‘ethnic’ by Australians including language. Anglo-conformity became the hallmark of ‘Dutch identity’ in Australia.[18] Most Dutch would say that “… if people come out here to make this their new country, they should … adapt themselves under all circumstances. When you are in Rome, do as the Romans do. You must fit in. After all, if you expect to further yourself economically and this country is prepared to give you a chance, then you have no right to be different.” These resettlement patterns, soon had the Dutch labelled most ‘assimilated’ and heralded as ‘model migrants’ because they were ‘invisible’!

Dutch Invisibility

By the 1970s Dutch invisibility was generally the accepted way to view Dutch resettlement in Australia. For example, on 2 February 1978, the Adelaide Advertiser noted:

“The typical Dutchman who came to Australia and assimilated for all his individualistic reasons, is a man without and out of history. He is ‘strong willed, fast thinking, often stubborn and possessed with a fanaticism tosucceed’. (1) His migration and assimilation, it seems, are natural expression of his character. Yet, this same Dutchman has only been in Australia since the 1950s: His migration was part of historic changes happening in both Australia and the Netherlands, and was negotiated and to a large extent financed by those governments.”[19]

Although the assimilated Dutch was a persuasive stereotype not all members of the Dutch community agreed with it. Many preferred like the Dutchman quoted by The Canberra Times on 13 May 1978 – to believe that the Dutch were the best [of all migrants] at playing the ‘assimilation’ game’.

Integration: Balancing both cutures!

Van De Berghe associates the tendency of an immigrant group to assimilate with the advantages in doing so. He claims that one of the conditions which encourages assimilation is an environment in which ethnic groups are clearly hierarchical.[20] Perceived from this perspective, Dutch invisibility in Australia can be viewed as the way they sustained their privileged second place on the preferential ladder.[21] Maintaining this distinctive adaptive strategy became even more effective when it appeared also to facilitate their access to the economic benefits of the Australian market place and to better treatment in the work force.[22] Moreover, so long as the dominion governments continued to foster a larger immigration than could be supplied from Britain alone, the policy would benefit the Dutch who everywhere were rated ‘second best’.[23]

Explanations by Dutch sociologists are equally compelling. They assert that Dutch people’s accomplished manner at making themselves invisible is a characteristically Dutch way of protecting their ‘inner inviolability’ in a society which stresses social conformity. Instilled via socialisation practices in the Netherlands, it positively evaluates a resolute commitment to hierarchy and self possession – particularly the Calvinist and Stoical values of discipline, frugality, industry, responsibility, obedience and indefatigable allegiance to leaders regardless of circumstances.

I associate the ‘aanpassen’ behaviour of first generation Dutch Australians with their socialisation within pillarized society they left behind. Each Pillars (Secular, Calvinist & RC) operated under the authoritarian leaderships of powerful educated elites, provided a strictly monitored cradle to grave schematic in which only the elites interacted across pillars!

The distinctive strategem this socialisation engendered among first generation Dutch migrants was to maintain their cultural integrity via the development of distinct public and private persona.[24]In the public sphere, de Longh maintains the Dutch in Australia, without exception, tried to be more Australian than the Australians.[25] The strategem is supported by recent research, which shows, despite the first generation’s sedulous Australian imitation, that they remained simultaneously, steadfastly very Dutch in the privacy of their homes. This peculiar way of maintaining their culture has lead some social scientists to speak of the Dutch culture as a ‘closet culture’. [26]

A direct result was that most Dutch failed to impart their language to their children. Nor did they introduce their children to Dutch clubs. Outward conformity to assimilationist mandates became the hallmark of ‘Dutch identity’ in Australia.[27]

Dutch Children – Language and Assimilation

As one child migrant notes, ‘assimilation was the policy and it certainly buried many feelings of Dutchness.’ For migrant children the ultimate outcome of assimilation ideology was divided values of the old country and the new country – the veneration of everything Australian and devaluation of everything ethnic.

As one child migrant notes, ‘assimilation was the policy and it certainly buried many feelings of Dutchness.’ For migrant children the ultimate outcome of assimilation ideology was divided values of the old country and the new country – the veneration of everything Australian and devaluation of everything ethnic.

Fitting-in was a difficult task when you were not accepted by Australians as an Australian and you did not want to be associated with those labelled inferior – the ‘New Australians’. Yet having foreign names, speaking very little or no English, dressing and having different food preferences set the migrant children apart. Dutch immigrant child was forced to make vital decisions about ‘belonging’ and ‘identity’ between the conflicting power sources of home and school.

What brings adult children back is the care of ageing parent many of whom have reverted to Dutch speaking after serious illness and as a natural process of ageing. The problem is they find it increasingly difficult to communicate with their parents. In addition, after their parent(s) death most find themselves unable to read the correspondence and documentation left behind. This is tragically important to family history research. The Dutch conformity and aanpassen was in a certain sense – a tragedy. Although deemed by Australia a success.

The Dutch made a major contribution to entrepreneurship via the trades in building construction and manufacturing industries shipbuilding), service and hospitality industries. The second generation are located throughout the employment spectrum including in the arts, literature, film making and politics.

So what has changed?

The Netherlands is now also a country of immigration. In ‘Immigrant Nation’ a 2011 text by Paul Scheffer he describes NL as a relatively conformist nation! And notes as striking, second generation Dutch Muslims lack of explicit ambition to take charge of the communities to which they’re assumed to belong (2011:127). Do they learn the language?

Conclusion

Understanding the history behind the cultural traditions that dominated our parents lives helps second generation Dutch Australians makes sense of their relationships with their parents and their struggle with identity and belonging. Understanding the difficulties and achievement faced by earlier migrant groups under the various resettlement policies provides the data for policy planning of resettlement services that will assist newcomers to make a seamless transition to the new lifestyle. For example to plan for the acquisition of both language or origin and receiving societies in at least 1/2nd generations would be a basic key to greater success. As such ‘Migration History Matters’ should continue to inform current policy. For the 270,000 Australians who now claim Dutch heritage it continues to ‘matter’.

[1] In fact, at the beginning of September 2011the resident population of Australia was 22,695,356.

[2] The number includes around 600,000 humanitarian programs entrants as displaced persons or refugees.

[3]. Walker Birckhead 1996, p. 2; Elich, p. 112. Both religions encouraged the exodus of large families as these were less likely to return.

[4]. Ibid; van Campen, Emigratie, 1954, p.132

[5]. J.H. Elich, ‘Aan de Ene Kant Aan de Andere Kant: De Emigratie van de Nederlanders Naar Australië 1946-1986’, Delft: 1987.

[6] Nonja Peters, Milk and Honey But No Gold, UWA Press, 2001.

[7]. Wim Willemsen, ‘Breaking Down the White Wall: The Dutch From Indonesia’ in N onja peters (ed). The Dutch Down Under 1606-2006, UWA Press: Perth, 2006, pp.132-149.

[8] ‘The false Bait: Australia land of Tomorrow’ De Waarheid. 28 January 1950.

[9] This is also noted by J. Menges, ‘Geschiktheid voor Emigratie:Een onderzoek naar psychologische aspecten der emigraantbiliteit’, Staatsuitgerverij, The Hague, 1959, p.1.

[10] Peters 2001.

[11] van Leeuwen, 1995.

[12] Ibid

[13] The Argus, 4 August 1951.

[14] Ibid

[15] Wim Blauw, Explanations of Postwar Dutch Migration to Australia, in Nonja Peters (ed), in The Dutch Down Under 1606-2006, UWA Press: Perth, 2006, pp.168-183.

[16] Jeannie Martin, The Migrant Presence: Australian Responses 1947-1977. Sydney. George Allen & Unwin, 1978.

[17] Cited by Van Leeuwin, 1995, p.44.

[18]. Nonja Peters, ‘Just a Piece of Paper: Dutch Women in Western Australia’ Studies in Western Australian History – August 2000.

[19] The Adelaide Advertiser, 2 February 1978.

[20]. P. van den Berghe, The Ethnic Phenomenon. New York, 1981, p. 259

[21]. J. Wilton & R. Bosworth, Old Worlds and New Australia: Post-war Migrant Experience, Sydney, 1984.

[22] Sociologist Van Den Berghe associates the tendency of an immigrant group to assimilate with the advantages in doing so and one of the conditions that he believes encourages assimilation is an environment in which ethnic groups are hierarchical.[22] Most migrants were unaware that the invitation by the Commonwealth Government for migrants to settle in Australia had ‘conditions’ attached in the form of ‘in-built preferences’.[22] Then again when you consider that between 1947 and 1974, 85 per cent of the British were granted passage assistance against 60 per cent of the Dutch, Germans, Maltese, Yugoslavs and Eastern Europeans and only 34 per cent of Greeks and 20 per cent of the Italians, clearly a ranking prevailed.[22] Perceived from this perspective, Dutch invisibility in Australia can be viewed as the way the Dutch kept their privileged second place on the preferential ladder, a strategy that also gained them better treatment in the Australian market place.

[23] Hendrik K van Leeuwen, ‘A Retrospective on Dutch Migration to Australia in the n1950s – a media perspective –and the reflections on selected Dutch migrants in Victoria’, MA Thesis, School of Visual Performing and Media Arts, Deakin University, Victoria, 1995.

[24]. Walker-Birckhead, 1996.

[25]. De Longh is cited in ‘It’s the Dutchness of the Dutch’, The Bulletin, Sydney, 1976.

[26]. Ibid.

[27]. Eidheim, pp. 41-2, notes that in Norway the Lapp identity is treated as illegitimate, and that these Lapps also refrain from acting it out in institutional inter-ethnic situations.