Three Dutch Priests in South Australia

By Elisabeth (Elly) Anderson – October 2006

Whilst researching the early history of a mainly Irish-administered Catholic community in the Adelaide Hills some years ago I was intrigued to find that the first documented visit of a priest, back in the 19th century, had been by a Dutchman. Being Dutch-born myself, I was especially pleased that Father Charles van der Heijden[i], a native of my old home province of Brabant, would be included in my (1987) book, On Fertile Soil, a history of the Catholic Church in the Stirling District.

Whilst researching the early history of a mainly Irish-administered Catholic community in the Adelaide Hills some years ago I was intrigued to find that the first documented visit of a priest, back in the 19th century, had been by a Dutchman. Being Dutch-born myself, I was especially pleased that Father Charles van der Heijden[i], a native of my old home province of Brabant, would be included in my (1987) book, On Fertile Soil, a history of the Catholic Church in the Stirling District.

The discovery of his presence in Adelaide so long ago has now led me to find out more about him and two other young Dutch priests who came to colonial South Australia in 1863.

The research for this article has proved to be a fascinating journey with some unexpected outcomes and numerous rewarding encounters by telephone, post and the internet, as I communicated with fellow authors, historians, archivists and far-away friends who helped me to piece together the story.

Elisabeth Anderson

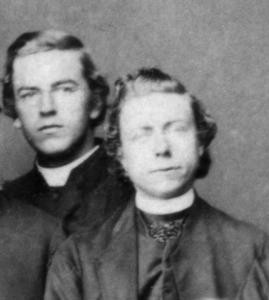

It began in 1862 when South Australia’s Catholic population was growing and the Bishop of Adelaide, Patrick B. Geoghegan, was concerned about the lack of priests due to deaths and infirmity among his clergy. In February that year he left Adelaide for Europe in search of recruits. On recommendation from a fellow cleric, he visited Utrecht in The Netherlands to appeal for help and as a result three “zealous and promising”[ii] young Dutch priests offered their services. Engelbert van Dieren (29), Theodore Bongaerts (25) and Charles van der Heijden (25) arrived in Adelaide in December 1863. Correspondence from the Bishop indicates that they travelled on a regular Adelaide trader (merchant ship) called The Harwich which took about 85 days to make the journey.

Engelbert van Dieren was born at Grave and ordained on 29 May 1858[iii]. He came to Australia with three years’ experience of missionary life and spoke English fluently. The Bishop felt that he was ready for anything. But for health reasons Engelbert would remain in Australia only till 1865 and then returned to Europe. He died at Handel in The Netherlands on 29 June 1900.[iv]

Theodore Bongaerts was born at Castle Ravenstein, completed his studies at Haaren and was ordained in The Netherlands on 14 June 1862.[v] He gave “sturdy service”[vi] to the Catholic community in South Australia until his death twelve years later.

Charles van der Heijden was born in Goirle, studied in Den Bosch and was ordained there on 30 May 1863.[vii] He was to conduct his ministry in various parts of Australia for about forty years.

Neither of the two younger priests spoke English at the time of their arrival although the Bishop felt confident that they would soon learn the language. However, he did not under-estimate the difficulties they would experience coping with a hot Australian summer and the mosquitoes which he described as “the torment of all newcomers”. So to help, the Bishop sent out “first rate bedsteads which will require only curtains…to secure them rest at night at least…”.[viii] He was also mindful of the culture shock they were likely to experience, acknowledging “there is no country in Europe where Catholic Clergy are so well off as in Holland – every respectable comfort is secured. They had no motive [for coming to Australia] but zelus animarum (zeal for souls)”, the Bishop wrote. He also described them as good theologians.[ix]

The Dutch priests ministered to a scattered flock in Adelaide and various country regions and covered vast distances on horseback, or in spring carts and wagons, making a significant impact on the communities in which they worked. Their names are perpetuated in parish registers of baptisms and marriages at which they presided.

But they were also caught up in some turbulent times in the Church in South Australia. It was a period of debt and dissension and it was noted with gratitude by the Bishop that Theodore was among those priests who showed unwavering loyalty and was not moved to join any of the clerical factions.[x]

Theodore showed the same loyalty to the fledgling Order of the Sisters of St Joseph when these women suffered antagonism from the church hierarchy and the excommunication of their co-founder Mary MacKillop. Theodore is singled out in Mary MacKillop’s biography as the Sisters’ friend, though this friendship must have come at some personal cost. The author Paul Gardner SJ writes:

Some priests supported her but this very friendship was a burden because she feared it might bring the displeasure of the bishop on those who offered it. One of the few things that moved her to indignation in these trying months was the persecution of Father Bongaerts for defending the nuns. She was deeply moved that he could not perform an act of kindness, even of justice, without wicked minds putting evil constructions on it. May God forgive them, she said, this is a cruel, wicked world. [xi]

As part of their ministry, the Dutch priests were required to conduct end-of-year examinations at Josephite schools, to further strengthen the connection.

And all this time, it seems, Theodore was suffering from intestinal cancer. After twelve years he succumbed to his illness and he died in Gawler, north of Adelaide, in 1875, aged only 37. The mission in his care at that time included three churches and five stations and his death left a huge gap in the pastoral care of his district. The Bunyip newspaper also stated that in the two years he had been stationed there:

…his earnestness in the cause of religion and charity and general good temper and generosity had raised himself to a high place in the opinion of every inhabitant of Gawler… his good name has extended beyond the pale of sectarianism and there are many Protestants who will unite with Father Theodore’s flock in lamenting his death.[xii]

These sentiments were certainly reflected in the days before, during and after the funeral proceedings where the locals gathered to pay “all the respect possible to their late beloved priest”[xiii]. The Josephite Sisters kept a reverend vigil at his coffin and a large procession accompanied the hearse to the Railway station, with children walking two abreast, dressed in black and white. Theodore bequeathed his property for the benefit of the orphans of his Gawler parishioners. He was buried in Adelaide’s West Terrace Cemetery.[xiv]

Charles was devastated by the loss of his friend. Theodore’s death, plus the privations he found in isolated parish life, proved too much and in July 1875 he moved to Victoria. Although he contemplated joining the Jesuit Order, the following year he became the first Parish Priest of Chiltern. This parish initially extended from Rutherglen to the Upper Murray, including Gooramadda and Granite Flat, in north-east Victoria. He travelled widely on horseback and sometimes covered quite hazardous terrain that is described well in Kathleen Dunlop’s 1978 book, The Parish that Wouldn’t Die:

“Perhaps the roads being dangerous and difficult to make out, it would be advisable for some one to meet me as I would like to give my horse a day’s spell on account of the long journey on the Friday…” he wrote to one of his flock when preparing for a visit to the Mitta Mitta River – Snowy Creek Junction and beyond in September 1876.[xv]

He never forgot the hardship of a journey to the Omeo plains at the height of the Australian summer of 1877. Many years later he still recalled how he had travelled in the company of a young mailman, aged about 16, a fearless horseman who had astounded him “beyond measure by his intrepid riding”. With the Boer War in mind, he wrote:

“I have often been thinking what an envious figure he would have cut to the English horse in South Africa had they seen what I saw”. He also recalled the Thunder and Lightning hotel where their horses “were treated to the most expensive meal ever paid for an equine animal and again on the plains where they had no water to drink, only a little port wine the season being very dry and the weather whilst I was there unbearably close”.[xvi]

It is little wonder that he is remembered as a “courageous priest” and a “true pioneer”.[xvii]

Letters still preserved show how his journeys were always preceded by much detailed planning. Then, after a “vigorous and fruitful”[xviii] ministry of twelve years in Victoria, Charles planned a trip back to his homeland and was farewelled in grand style by the local community. Among those present were “between fifty and sixty of the most influential citizens of the district, amongst whom were many ministers and members of other denominations assembled to do honour to the reverend gentleman.” He delivered a long speech in fluent English “something of a feat for a man who couldn’t speak a word of the language when he volunteered for Adelaide twenty four years earlier” in the view of historian Kathleen Dunlop Kane.[xix] Nevertheless, even after almost a quarter of a century in this country, he still described himself as a foreigner.

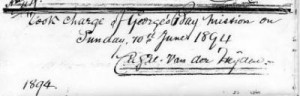

On his return to Australia Charles worked in Armidale and Sandhurst. Then, after a seemingly bleak period in his ministry when he was out of work and almost out of money, he moved to Tasmania, where he served at New Norfolk from 1892 till 1894 and the St George’s Bay Mission from 10 June, 1894, till April 1903,[xx] ever conscious, it seems, of his status as a trail blazer – his signature on a document in Tasmania being preceded by the words The Pioneer:

A notation from Charles van der Heijden recording his appointment in 1894. Kathleen Dunlop Kane in The Parish That Wouldn’t Die described his writing as firm and distinctive and a delight to read. (Image by courtesy of Hobart Diocesan Archives ©)

A notation from Charles van der Heijden recording his appointment in 1894. Kathleen Dunlop Kane in The Parish That Wouldn’t Die described his writing as firm and distinctive and a delight to read. (Image by courtesy of Hobart Diocesan Archives ©)

It is recorded in a number of publications and documents that Charles van der Heijden died in 1903. But in the Launceston Library there is a copy of The Examiner newspaper, dated 30 March 1907, which carries a notice of his death on 19 January 1907, in Antwerp, Belgium, aged 68. Perhaps the discrepancy is due to a lack of historical Catholic data in Tasmania for that period.

Of the three pioneer priests, Father Charles Martin Gerard M. van der Heijden had, at the age of 24, been the first to put up his hand for Australia [xxi] and, at the age of 68, the last to survive. He clearly experienced the ups and downs of life during his time in Australia. According to archival information in Melbourne, at some stage he even made money from tin mines. It is just a snippet of information and one can only imagine that it assisted him in difficult situations or perhaps to return to Europe.

My attempts to fill in the last five years of his life have been unfruitful so far. One could assume that this missionary priest had simply gone home on his retirement.

It is interesting to note that at the time when the three Dutch priests left for Australia in 1863 to work amongst the Irish Catholics of South Australia, two Irish students were admitted to their theological college in The Netherlands to prepare themselves to minister to Dutch Catholics at the Cape of Good Hope[xxii] – on the face of it ironic but in Charles’ own words:

“A beautiful instance of not only mutual kindly feeling,

but especially also of Christian charity” [xxiii]

End Notes

[i] His name is anglicised to van der Heyden in most archival records in Australia.

[ii] Press, Margaret M. RSJ 1986 From Our Broken Toil. Catholic Archdiocese of Adelaide in Adelaide:

South Australia. P143.

[iii]Nic Klaassen, Dutch Priests for South Australia 1996-2006, www.southaustralianhistory.com.au

[iv] Ibid

[v]Ibid

[vi]Press, Margaret M. RSJ 1986 From Our Broken Toil. Catholic Archdiocese of Adelaide in Adelaide:

South Australia.P.198.

[vii] Anderson, Elisabeth 1987 On Fertile Soil. Catholic Parish of Stirling SA: Stirling South Australia. P.

47.

[viii] Dunlop, Kathleen Kane 1978 The Parish That Wouldn’t Die. Parish of St Mary’s: Chiltern, Victoria.

- 8. (Engelbert Bongaerts’ name appears as Englehart Bongaerts in this publication).

[ix] The letter Geoghan to Smyth, dated 25 September 1863, is courtesy of, and copyright retained by,

Adelaide Catholic Archdiocesan Archives.

[x] Press, Margaret M. RSJ 1986 From Our Broken Toil. Catholic Archdiocese of Adelaide in Adelaide:

South Australia. P.196.

[xi] Gardner, Paul SJ 1994 An Extraordinary Australian Mary MacKillop E.J. Dwyer (Australia) Pty

Ltd. in association with David Ell Press: Alexandria, NSW. P.108.

[xii] The Bunyip newspaper, Gawler SA 22 Jan 1875.

[xiii] Ibid

[xiv]See photo www.southaustralianhistory.com.au Dutch Priests for South Australia (author Nic

Klaassen).

[xv] Dunlop, Kathleen Kane 1978 The Parish That Wouldn’t Die. Parish of St Mary’s: Chiltern, Victoria.

P.12.

[xvi] Ibid p14

[xvii] Ibid p14, p16

[xviii] Ibid p15

[xix] Ibid p16

[xx] Archdiocese of Hobart Museum and Archives.

[xxi] Charles spoke of this in his farewell speech at Chiltern in 1888, a report of which appeared in The

Advocate on3 March 1888, reproduced in The Parish That Wouldn’t Die 1978, by Kathleen Dunlop

Kane, p. 9.

[xxii] Ibid

[xxiii] Ibid

Elisabeth Anderson would also like to acknowledge the following for their contributions and input into this story:

Adelaide Catholic Archdiocesan Archives

Patricia Sheahan B.A. DipEd (Melb) Adv Dip Ed (Adelaide), of Roseworthy, SA, author of A History of the Gawler Catholic Parish to 1901, 1998

Indigo Council

Chiltern Athenaeum Museum

Sister Carmel Hall, Archdiocese of Hobart Museum and Archives

Bill and Nell de Jong of Norwood, Launceston, Tasmania

Carolyn Gutteridge, Catholic Parish Launceston

Rev John Ware, Catholic Parish of Rutherglen, Victoria

Rachel Naughton, Archivist and Museum Manager, Catholic Archdiocese of Melbourne, who sourced information from The MDHC Summary of The Advocate and 19th Century Priests A – Z. She advised that there are van der Heyden letters in the Sandhurst (Bendigo) Diocese.