In May 1950, a group of 10 men, and their wives, met in the residence of Eerke van der Laan in the city of Groningen. They had met several times before, and during the war years had learned to know and trust each other. Now they were discontented, but hopeful.

The effort these men had put into resisting the tyranny and brutality of the Nazi occupation went unrecognised after the war. The risks they had taken, the suffering they had endured, the pain of losing loved ones to the evil hand of the oppressor, were not merely ignored, they were belittled. There was no reward for their effort. Worse still, the rewards, the spoils of war, went to those who had behaved as cowards during the dark years.

The group decided, in response, that they would rather live somewhere else in the world. Beside their discontent, they were worried that another war was imminent. The Russian troops were massed quite close to their home. It was estimated that the Russians could, after only 24 hours of battle, count the English Channel as their western border.

The group was keen to avoid this situation—to endure another occupation was something to be feared. Thus they considered emigrating: leaving their place of birth and all they knew, leaving for somewhere else in the world where they could live honestly and in peace. They had considered the possibility of moving to Surinam, Papua New Guinea, South Africa, and various other places on the globe, but had chosen Australia, after a first hand report was given to them.

Friends of friends had heard of a Dutchman who had lived in Australia for more than 12 years. This man was renting a house not far from Groningen in order to complete doctoral work into the weaving industry in the province of Twente. Groningen is a long way from Twente, but he had to choose this house because there was still a tremendous shortage of housing in the Netherlands as a consequence of the war.

The visitor’s name was Jan Boot. He had addressed the group earlier in the year, and convinced them to make their new home in Tasmania. Again he extolled the virtues of Australia in general and Tasmania in particular, and the opportunities for anyone who was willing to work. There were many things he didn’t tell them, such as the abyssmal quality of the coffee, and the lack of decent green beans, and that their hammers were too light to hammer nails into Australian hardwood.

Also at the meeting were two men, almost brother’s in law, who had needed to hide, from time to time, from the Gestapo. One of these men, Jetze Schuth, had built a trapdoor in the floor under the bed of Reg’s parents, using his cabinet maker’s skills. When there was a razzia, he and any others in the house who were at risk of arrest, could fall through the floor and hide under the house. Jetze normally slept at Reg’s place, and both often slept in the hidden space under the floor.

After the war, Jetze and his best friend Reg Doedens, neighbours, had been volunteers in the Dutch army, serving in Indonesia from 1945 – 1948, protecting the population from violent independence-minded militias that were determined to seize control of the country before a rational handover could be achieved. They had heard about the meeting through church friends, and at the end of the evening, they were excited. The vision of possibilities in this unknown land thrilled them. There were, however, some issues to deal with.

Reg had contracted to buy his boss’s business, but his boss agreed, the next morning, to tear up the paperwork and release him. Reg then had to cycle 20 kilometers to the place where his fiancee, Corrie Sikkema, was working. She had an inkling of the problem on his mind, as two of her brothers had also been at that meeting and had determined to heed the call of the new land, and so she had had time to consider the matter. To his delight, she had chosen against a life of non-descript predictability for a life of adventure – she was ready to go.

Corrie was best friends with Elly Doedens, only sister of Reg. Elly had trained as, and qualified as a psychiatric nurse during the war years. However, she had been called home to help her father in his tailoring business, where the future seemed un-inspiring. Besides, petty snobbery in her home town irked her. Her father, in the meantime, had an eye on the Russian threat, of which there was a daily reminder in the fleet of planes flying over their town, headed for Berlin with all the supplies that city needed, and so gave his blessing to the adventure.

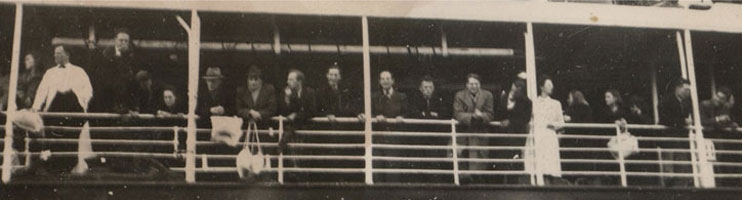

The two couples resolved to marry on the 29th of June, 1950, in a double ceremony. The men then flew to Tasmania, less than five weeks later, with two of Corrie’s brothers, Wim and Henk, to prepare housing for the families that would follow by boat. They were all convinced that they would never return, mostly because they had spent all their assets on the fares – there would never be enough money to afford a return trip. Yet they went happily, and confidently, despite a lack of money or English language skills. Jetze was thirty years old, Elly was twenty-five, Reg and Corrie were both twenty-six, and Corrie’s brothers were in their early twenties.

Eerke and a colleague had gone to Tasmania first, in early June, and after spying out the land and potential opportunities, had opted to purchase land in Kingston. Living conditions were primitive – the men had to sleep in tents, cook over open fires, and hang their was on line strung between the trees. They took time out on Saturdays to see their new country, to go to the football, to have a snow ball fight on the top of Mount Wellington with some locals, just for fun (their military training paid dividends). In the meantime, the brides sailed with the families, Elly discovering on the way that she was not prone to sea sickness, but that she was suffering from morning sickness.

The first of eight babies was born in the new year in the new country. The third baby was not healthy, and died after only two days. His death was one of the first amongst the Dutch migrant community, but their comfort and care, and the demands of the first two, helped them move on.

Elly and Reg’s father died in 1955, and they brought their 68 year old mother out in 1959, ostensibly on a holiday. After eight years of holiday and constant quibbles about the poor state of local facilities, especially footpaths, mother returned to her home town. However, things were not as rosy there as memory pictured them, and so she returned to Tasmania for the rest of her life, without any more complaints. In the meantime, the other two brothers, Dan and Max, had also migrated to Tasmania with their families.

Australians proved to be very friendly and helpful. The migrants had been encouraged by their government to leave, and by the Australian government to come. The housing situation was difficult, to say the least, and sharing was the order of the day. Couples shared houses, families shared houses, families shared children. Feast days were celebrated together – invitations were not given out because everybody was always invited to everything, ‘us and them’ did not begin until the 1960s, when there were too many, with too many unshared experiences, for everybody all to be ‘us’.

Eerke and his colleagues had made friends on their first day in Kingston with Archie Smith, and he was very helpful to them. Amongst other matters, he had a holiday shack in Howden – not so far from Kingston. To help with the desparate need for housing, he allowed them the use of this shack, and the two honeymooning couples were the first to share there. Little did they expect that, fifty years later, they would be living in homes they established for themselves on the opposite shore of North West Bay, barely a kilometre as the crow flies from their starting point.

A few months later, early in 1951, Jetze and Elly were allocated a house in Little Groningen. This was what we now call a subdivision, but only a roughly formed road, and water and electricity were laid on. Footpaths, sewerage and telephone were all on the dream list. The land had been purchased from a farmer – a portion of his land that was still bush as it was not suitable for cropping. It was the farmer who dubbed the hamlet, and also suggested that the approach road be called Groningen Road. The migrants found it useful to be together initially, but all aspired to own their own block of land, and to build their own homes.

After almost ten years in Little Groningen, Elly and her family moved to the house in central Kingston that Jetze had built in his spare time. Most of their friends lived within walking distance, although the family did have access to a Commer van owned by the building company. Reg and Corrie lived two doors down. Church and school were also within walking distance, so there was no need to ferry children anywhere except in season to soccer on Saturday mornings.

Elly was keen to support the Association for Christian Parent-controlled Schools. She firmly believed that the education of her children was the responsibility of the parents, and so it was up to her and Jetze to decide what sort of teaching her children should have. They believed that the school should be an extension of the home, not a mission field for the church, nor a place to raise an elite. The role of the state was only to stipulate the standards, the levels to which children should be taught, and to distribute the resources available for education to all children equally. This was the education model they had left behind, not a new invention, and they worked hard with other parents to achieve the same model here. All of her children attended the school they established, Calvin Christian School.

The Commer van was well used, mostly to transport the South Eastern Builders men to the building sites, but also recreationally. Holidays were typically spent working on the house or garden, but day trips were also scheduled. The van was shared with other families. A day trip that is still recalled with amazement was made to Port Arthur in 1963. Jetze and Elly and their children, plus two other couples and their children, and a maiden aunt, twenty-three people all told, and all the necessary food and drink, squoze into that van for a journey of ninety minutes each way, and they all had fun.

There was plenty of bush behind the house, and the children grew up playing there, inventing games, gathering material for the annual Bonfire Night, and making cubby houses. The children were also constantly with their friends, all neighbours, after completing chores, and during school holidays could expect lunch in whichever house they found themselves – they only had to answer the question – “does your mum know where you are?” with a “yes”. There were no fences between the houses, and no locks on their doors.

After settling in to her own home, Elly discovered craft—handwork that could be done for its own sake rather than of necessity. A visitor from the Netherlands, a maiden aunt, lodging for a while with her brother, a neighbour, had demonstrated craftwork and how to pass the skills on to children. So began a love affair with needle and thread. At first, it flowered briefly, because the opportunity to learn some pottery skills presented itself. This began as an Adult Education course, and here another remarkable thing began. The course was open to all, and so the circle of people Elly met with regularly included non- Dutch, and non-church, people. All of them were Australians, although some had only had this status for a few years, like Elly. The potters could not continue using the premises of the Kingston Primary, and so, after consulting with Jetze, who was very amenable, they established in a corner of his workshop.

Craft Group

Previously, Elly had been a member of the church Ladies Guild, where all present were church members, almost all Dutch migrants with young families, sharing the same joys and difficulties. The potters group was the first of many craft groups in which the love of the craft was the priority, and so there was opportunity to share different joys and concerns as they worked together. Although Elly often provided the venue for the craft groups, she was never the leader or initiator. Craft skills were shared and taught to others in the group by group members.

In the early 1970s, until the late 1980s, a Christian revival swept through Kingston. It was not especially led by the main four church leaders (Reformed, Anglican, Roman Catholic and Uniting), although these men met every week for Bible study and prayer together and became quite an intimate group. However, the Spirit was moving, and it became normal for people to attend meetings in other churches, and to discuss aspects of the Christian life, even when they met each other in the shops. Bible study and prayer groups sprang up in large numbers, some of them across church boundaries. The Anglicans organised a ‘Life in the Spirit’ seminar, amongst other events, and Elly loved it all. Space was made for the expression of emotion in daily life, and in spiritual life, which was, they realized, the same. Spiritual life was released from the shackles of Sunday, from the awe and reverence that was expressed on Sunday, from the separation from daily life. Jetze was more reserved, but didn’t disapprove of the new understanding, and Elly’s mother was quite accepting because she had experienced a similar revival in Groningen immediately after World War One.

In this period people also sought practical expression for their beliefs, and so two Reformed Church women began a women’s shelter which they called Jireh House. This was a fairly new concept in the mid 1970s, and it took some years to find the right formula to make it useful. Elly was involved from the beginning, both in prayer groups and in the hands-on things that needed doing to assist women (and their children) who needed to re- start their lives.

After some twenty years in her new homeland, Elly and Jetze decided to return to the Netherlands, mostly at his behest to see his family. The experience of the country, the way people lived (but not her in-laws) resolved her to never visit again. There was nothing there to attract her, she simply did not feel at home. Jetze visited again some five years later, as he was rapidly becoming blind as a consequence of his diabetes, and so Joan, the youngest daughter, travelled with him. A consequence of Jetze losing his sight and the multitude of medical appointments that were part of that process meant that Elly, at fifty years of age, had to learn how to drive a car – a novel experience.

By this time Jetze was home full time because he could not work as a carpenter, let alone as a cabinet maker, the work he preferred and had done so well. He trained himself to do many of the household chores despite his limited vision, and this freed Elly to do other things. This became their way of life until Jetze died in 1997. In the meantime, as their home was centrally located, and their circle of friends so wide, and they could be counted on to be home, a lot of time was spent hosting visitors. During the day, the key was in the door if they were home, and the house sometimes seemed like a train station, with people coming and going. A love of gardening came to the fore in this time, and discovering and sharing plants was part of the delight.

Craft work also continued, but it was now spinning. Elly even kept a black sheep, for its wool, in this time. This was not unusual – there were always chickens, besides the usual pets, in her home or yard. The craft group eventually evolved into a quilting group, under the tutelage of Marianne Whitty, a childhood friend of Joan. The initial quilts were made as small squares, crotcheted or knitted or sewn. The individual squares made by the members were then arranged and sewn together, and the whole donated to a good cause to be auctioned as a fundraiser. A good cause in this case usually meant the Calvin School or Jireh House. Today there is still a group that meets weekly, using a room in the church building, although, as it has always been, not all members are Christians. The love of the craft and the time together are what is important. They currently knit and crochet blankets for Christian Missions in Israel.

Amongst all the migrant families from the early 1950s, Elly’s family is unique in at least two ways. In the first place, all the birthdays, and the wedding anniversary, are in the first half of the year. That’s just by the way. More importantly, all of Elly’s children live in Tasmania. The eldest, Anna, lived for a while in Alice Springs because her husband had work there, and then lived on Elcho Island, in response to a Divine calling, after her husband died. The second eldest son, Danny, lived for a while in Adelaide because of a girl he met there during his travels. But now they all live in Tasmania. They acknowledge the desire for adventure that brought their parents here, and agree with their parents that this is simply a wonderful place to live. There is no need to look elsewhere – the place chosen by their parents is more than sufficient.

Danny bought his mother’s house after it became too big for her alone, and all the boys worked together, combing their trade skills, to build a new house, custom designed for their mother’s needs with a very large living area, and a large room for craft work, and an elevated garden. The house is close to a congregation of the Reformed Church, and the street is level, and the footpath properly made, so there is no need to drive to church.

The children all visit their mother, some daily, some less often. Joan now lives with her mother, as Elly’s mobility decreases. Nineteen grandchildren and thirteen great grandchildren ensure that the front door swings open often, if the key is in the lock.

- Interviews and archival research: Kees Wieringa, 2014.

- Funded: Your Community Heritage Grants, The Department of the Environment, Canberra.

- Interview Series 2014: organised by Dr Nonja Peters, History of Migration Experiences (HOME), Curtin University, Perth Western Australia.