Netherlands East Indies (1939 – 1946)

Internment, resilience and survival: The story of Dirk Drok who helped to uncover the Batavia and a key contributor to Voyage to Disaster, and his wife, well-known painter and ceramicist, Kitty Drok

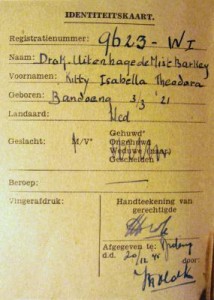

Why might a young baby less than a year old be interned in a prisoner of war camp? The answer was for his own safety. As the underlying reasons are complex, we start this story with his loving parents, Evert ‘Dirk’ Drok (1915–1988) and Kitty Isabella Theodora Uitenhage de Mist-Barkey (1921–2001) who lived in Java, in the former Netherlands East Indies prior to the Pacific War (1942–1945).

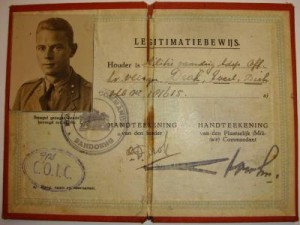

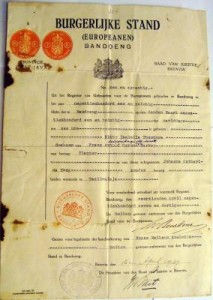

Dirk was born in Dalfsen, Holland, in 1915 and would have learned much about the East Indies in his youth, as his father had travelled there in the early part of the 19th century. Kitty was born in Java in 1921. Her father Herman Barkey was Dutch and owned a rubber plantation near Malang, and her mother Johanna (Jo) Uitenhage de Mist was born in Java with a Dutch father and Chinese mother. Kitty and Dirk met in 1939 when he was a dashing 2nd Lieutenant in the Netherlands East Indies Military Airforce. They married in 1941 and their son Arnold was born in February 1942.

Arnold’s birth coincided with the fall of Singapore, and it was a matter of weeks before the Japanese invaded Java in March 1942.

The Japanese quickly overwhelmed Dutch and Allied forces and, when the Dutch surrendered, 40,000 military men and 100,000 civilian men, women and children were interned in Japanese POW camps for the next three-and-a-half years. Dirk was interned almost immediately as he was in the military, and Kitty was also interned as she was his wife. They were sent to separate camps, one for women and the other for men and young boys over ten to twelve years of age. Jo and Herman were given a temporary reprieve as rubber was a valuable commodity to the Japanese and they were needed to work the plantation. In this chain of events Arnold was separated from his parents to live in relative safety with his grandparents on the plantation for the rest of the year.

It is well documented that the Japanese actively provoked Indonesian dissent towards the Dutch and the situation became so volatile that Jo and Herman decided to place themselves in a POW camp for their own safety. Jo took Arnold into ‘Solo Kamp’ in early 1943 where he was reunited with his mother Kitty, and Herman entered one of the men’s camps, the name of which is unknown.

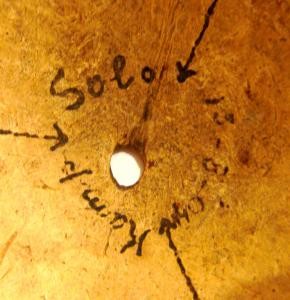

As will soon become clear, much of this story emanates from Arnold who is now living in Perth, Western Australia. It not surprising that Arnold who was interned at such a young age has sparse memories of this time, but he vividly remembers a shootout between the Americans and the Japanese within the POW Camp, where Arnold, his family, and other Dutch internees were caught in the middle. This would have been around the time of the Japanese capitulation in August 1945. They were taking cover under wooden bunk beds and when one of the bullets hit the ceiling and fell to the floor Arnold dived out to catch it “as a treasure”. He still remembers the orchestra of voices yelling at him to get back under that bed! Beyond that, his memories are hazy, and he knows surprisingly little of his parents’ experience of war. Like so many other people, Kitty and Dirk did not elaborate on time spent in a prisoner of war camp, and Arnold now finds it difficult to distinguish between his own sparse memories and the little that was revealed to him. When Kitty died in 2001, Arnold was surprised to find a leather bag containing Netherlands Indies Welfare Organisation for Evacuees (NIWOE) ration books and meal vouchers, two baby shawls from the POW camp, a beautifully embroidered sheet, gold capped teeth (typically used as currency in camp situations), food bowls made from coconut shells; early photographs, passports, postcards, and tiny letters written by his father on rice paper and smuggled to Kitty interned in a separate camp. All these things had been hidden for some 55 years and when found after his mother’s passing, Arnold and his brothers could only ponder over their particular history and personal meanings.

These keepsakes tell us of much about Kitty’s experience of war, the conditions of life in POW camps, the relationships between family and fellow internees, and a measure of the wider context of the war and post-war period in Java during this time frame. The baby shawls are appliqued with different materials and embroidered with Arnold’s initials, A.D., and ‘Pinkie’, his nickname as a child. The material scraps tell a story within themselves. The characters present as Indonesian, yet with fair hair. The koala figures tell of the association of the East Indies with Australia starting with the Batavia in 1689, and the children from the East Indies who were educated in schools in Perth, Western Australia including St Hilda’s, Presbyterian Ladies College and Wesley College. The children travelled back and forth between Perth and Java or Singapore, the latter beautifully detailed in Juliet Ludbrook’s 1999 book, Schoolship Kids of the Blue Funnel Line.

Did Kitty or grandmother Jo bring the material with koala images into the camp, or were the quilts made from scraps of material collected from a number of women who were supporting each other in a time of great difficulty? What is very evident is the tangible expression of love and care for baby Arnold in spite of the difficulties, the deprivations, and the well-documented abusive behaviour of camp commandants.

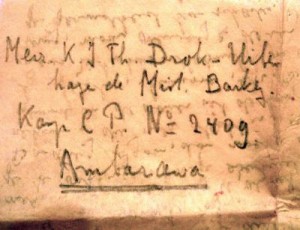

The coconut shells served as bowls and plates, with their detailed engravings revealing a personal and social history. In the centre of the bowl, is ‘Solo Kamp’ with Arnold’s internee number, 2604. Around the rim of the bowl are the names, K. I. Tr. Drok (Kitty); J. C. Barkey (grandmother Jo) and Arnold. The images in the lid of the bowl are open to interpretation—but they suggest a loaf of bread at the centre, a slice of bread to one side and another dish beneath.

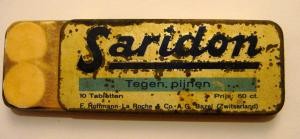

Among Kitty’s keepsakes, were a number of small items that would have been so very valuable to an internee. These include a nail file, a notebook, an ivory brooch, a small tin of Pethedine-based Saradon tablets and a photo of her husband Dirk, interned in another camp.

In addition to these largely practical items were a number of gold-capped teeth typically used as a form of local currency between POW internees and guards or local people who would then smuggle much needed food and medicines into the camp in return for gold. Those in the camps had little choice: it was an extreme situation in which out-of-the-ordinary measures needed to be taken to survive. It was not unusual for the Dutch to be given just one handful of rice a day and many spoke of supplementing their meagre rations with snails, grass, and other kinds of plants. They say the Japanese were very fearful of those who were diseased, preferring to keep their distance, which left internees in a good position to extract the gold that would help keep others alive.

In addition to these largely practical items were a number of gold-capped teeth typically used as a form of local currency between POW internees and guards or local people who would then smuggle much needed food and medicines into the camp in return for gold. Those in the camps had little choice: it was an extreme situation in which out-of-the-ordinary measures needed to be taken to survive. It was not unusual for the Dutch to be given just one handful of rice a day and many spoke of supplementing their meagre rations with snails, grass, and other kinds of plants. They say the Japanese were very fearful of those who were diseased, preferring to keep their distance, which left internees in a good position to extract the gold that would help keep others alive.

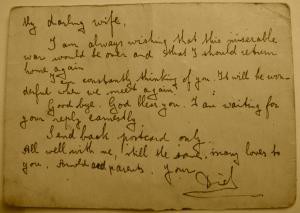

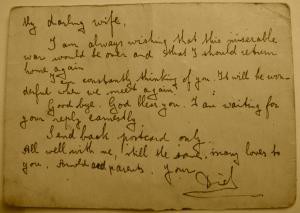

There were also very special mementos including post cards written by Dirk which would have been delivered by the Red Cross, and tiny letters written on rice paper that had been smuggled into Kitty’s camp. Once can easily imagine Kitty’s joy at receiving news from Dirk, plus the relief of finding he was still alive. The rice-paper letters also show Dirk’s sheer determination to remain in contact with his loved ones, his resilience and his capacity to outwit his captors by finding a way to smuggle letters with detailed information into Kitty’s camp.

“My darling wife,” each one began. “Last night I got a message that you are healthy and well in Ambarawa. Kitt it was like a shock that went through me when I heard it. I was afraid because of all those stories that went around about the women in Camp CP. This was the best news I could get on Queensday.” Dirk repeatedly expresses his delight in hearing that Kitty, Arnold and Jo are still alive. “Kitt my girl you don’t know what this meant to me when I heard all this.” He explained that he’d lost considerable weight, that his health had improved when he was transferred to the deserted Tjihapit women’s camp in Bandung that was to hold 2,800 prisoners of war. Here the food and accommodation was sufficient. Dirk hoped that on release they would all be able to make their way to Bandung. He’d heard news on the grapevine that the Red Cross were helping to send the sick women to Bandung’s Boromeus Hospital. “In case you are free and decide to go to Bandung, than you have to count on a four day trip, not too good … be very careful, take no risks. Deal according to the information you can get. It is still not very safe outside and we have to take all precautions until the Allies have taken over … It is a pity that I can’t leave the camp to find out more about Pop and aunty Willy, we are just not allowed to leave. However I do all that is possible to make contact.” It would have been difficult for Jo to hear that Dirk had no news of her husband Herman, no knowledge that he was still alive. Dirk was well aware that many communications would strategically leave out information that might add to anxiety of loved ones, and thus one can understand that he would ask Kitty: “Tell me how much you weigh and if you people really are healthy and strong”. “Darling wife I don’t know when we can meet again, but I hope it will be very soon. Lots of love and a kiss, also for Mum, Arnold, give them a hug, Dirk.”

In contrast to the copious information packed into the rice paper communications, the content of the postcards delivered through official channels via the Red Cross was more cautious and reserved. Undeniably heartfelt, the content focused on expressions of love and endearment, queries about family members, and presented evidence that the person writing was still alive. Most cards were written in English or Dutch, although some were written in Malay— so similar to yet different from Bahasa Indonesia, now the official language of the Indonesian Republic.

In contrast to the copious information packed into the rice paper communications, the content of the postcards delivered through official channels via the Red Cross was more cautious and reserved. Undeniably heartfelt, the content focused on expressions of love and endearment, queries about family members, and presented evidence that the person writing was still alive. Most cards were written in English or Dutch, although some were written in Malay— so similar to yet different from Bahasa Indonesia, now the official language of the Indonesian Republic.

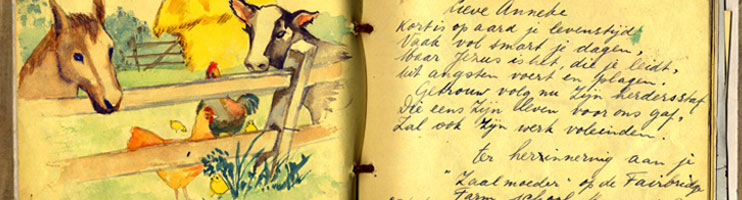

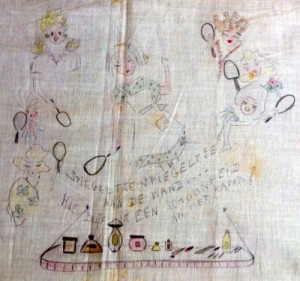

Dirk clearly had his wits about him as he developed the networks to smuggle letters across Java without being detected. Kitty was also resilient, but in a different way. On one hand she had the support of her mother Jo and also a clear determination to survive in order to protect her baby son. She had also been given advice by a wise old Indonesian man at the outset of war who told her the more she was able to treat war as a ‘game’, the more likely she was to survive. In adapting this advice to limitations and possibilities of life in Solo POW camp, Kitty developed her creative skills and it is possible that her time in the camps helped pave the way for a successful artistic career to come. One can see an example of her early art in ‘Revue Solo’ – a small embroidered tablecloth converted into a sheet for Arnold – in which her flair for design and performance clearly shines through. It only took a few coloured pencils for Kitty to express rhythm, movement, form and humour to the characters in her sketches. Revue Solo was a parody, a satire, a visual performance, that helped turn life in a POW camp into a game.

Dirk clearly had his wits about him as he developed the networks to smuggle letters across Java without being detected. Kitty was also resilient, but in a different way. On one hand she had the support of her mother Jo and also a clear determination to survive in order to protect her baby son. She had also been given advice by a wise old Indonesian man at the outset of war who told her the more she was able to treat war as a ‘game’, the more likely she was to survive. In adapting this advice to limitations and possibilities of life in Solo POW camp, Kitty developed her creative skills and it is possible that her time in the camps helped pave the way for a successful artistic career to come. One can see an example of her early art in ‘Revue Solo’ – a small embroidered tablecloth converted into a sheet for Arnold – in which her flair for design and performance clearly shines through. It only took a few coloured pencils for Kitty to express rhythm, movement, form and humour to the characters in her sketches. Revue Solo was a parody, a satire, a visual performance, that helped turn life in a POW camp into a game.

Kitty was making fun of life in the camps, with the women dancing in the vegetable garden, proudly parading past the locked gates, singing as they cooked and cleaned, and walking the tightrope on the clothes line after washing their clothes.

She was able to look at the situation around her with a degree of humour, despite the very harsh realities of starvation, confinement and deprivation. The sketches also reveal a number of frustrations: women queueing for washing and toiletries, and wondering how to retain any sense of femininity and former identity. “Mirror, mirror on the wall … how do I stay beautiful in the camps?”

A parody of life in the Solo POW camp, Java, 1942-1945 (‘Revue Solo’, Kitty Drok ©).

Japanese capitulation and evacuation to Australia

Life changed unexpectedly with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. The country was thrown into further turmoil following the Japanese capitulation as the Indonesian people strongly asserted their independence and the Netherlands struggled hard to retain its former colony. Australian, American, British and Gurkha forces attempted to reach embattled civilians and ex-internees, yet there were 229 known prisoner of war camps throughout South East Asia and it could take months to reach, let alone help, them. Nothing has been recorded about the release of Kitty, Dirk, Arnold, Jo and Herman from their respective camps. However, it is widely known that the carnage during this time was unspeakable as thousands of Dutch nationals and others were killed en masse. It is not surprising that those who survived chose not to talk about the terror and danger of this time to their children and grandchildren. Their main goal was to put the past behind them and get on with their lives.

For more information about this time-frame, see: “‘These Were Wild Times’: The evacuation of Dutch Nationals from the former Netherlands East Indies to Western Australia, 1945-46” to be published in 2016.

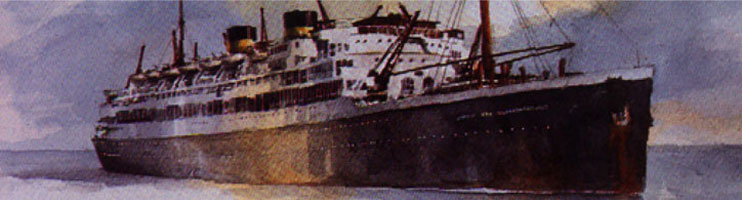

The Dutch who survived were mostly evacuated to Singapore, India, Ceylon and the Netherlands with some 6000 entering Australia for temporary ‘recuperative purposes’ from late 1945 to early 1946. They arrived by formal and informal channels, in Catalina and Qantas Flying boats, Dutch Dornier boats, Lokeheed Lodestars, B25 Bombers, DC Tens, submarines, cargo and hospital ships – in just about anything that had the capacity to fly or float. Arnold was nearly four years of age when he stepped off an old cargo boat onto the Fremantle Wharf with his grandparents Jo and Herman, and his mother and father, Kitty and Dirk Drok, on 20 January 1946.

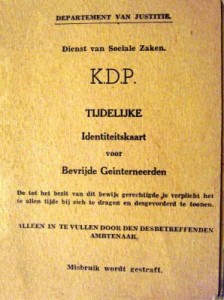

During the war years, a Netherlands East Indies government-in-exile was established at Camp Columbia in Queensland which was well prepared for the arrival of the East Indies Dutch. They established the Netherlands East Indies Welfare Organisation for Evacuees (NIWOE) whose role it was to receive and process evacuees, to pay all expenses associated with their ‘recuperation’, and to organise accommodation in private homes, hotels and boarding houses. It is likely that the Droks were met by NIWOE representatives or members of the Australian Red Cross and then taken to NIWOE state headquarters based at the Cloisters, St Georges Terrace, Perth to be formally processed as evacuees. Dirk and Kitty had arrived with a temporary ID card issued by the Dutch ‘Departement Van Justitie’.

During the war years, a Netherlands East Indies government-in-exile was established at Camp Columbia in Queensland which was well prepared for the arrival of the East Indies Dutch. They established the Netherlands East Indies Welfare Organisation for Evacuees (NIWOE) whose role it was to receive and process evacuees, to pay all expenses associated with their ‘recuperation’, and to organise accommodation in private homes, hotels and boarding houses. It is likely that the Droks were met by NIWOE representatives or members of the Australian Red Cross and then taken to NIWOE state headquarters based at the Cloisters, St Georges Terrace, Perth to be formally processed as evacuees. Dirk and Kitty had arrived with a temporary ID card issued by the Dutch ‘Departement Van Justitie’.

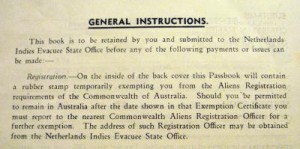

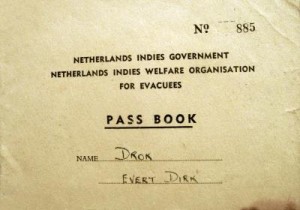

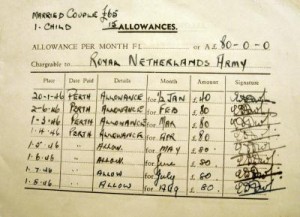

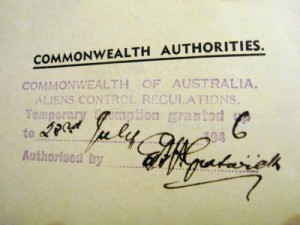

They would have then been issued with formal documentation – The Netherlands Indies Government / Netherlands Indies Welfare Organisation for Evacuees PASS BOOK – which details the conditions, facilities and services available to evacuees for their temporary recuperation in Australia. From Dirk Drok’s PASS BOOK, we can see the incoming Dutch were temporarily exempted from the Aliens Registration requirements; that there would be payment of approved medical, dental and hospital expenses; that they had to notify the NIWOE State Officer of their travel plans, for their journeys to be authorised and for their fares to either be paid or refunded. The evacuees were responsible for payment of their own accommodation, otherwise deducted from their allowances.

They would have then been issued with formal documentation – The Netherlands Indies Government / Netherlands Indies Welfare Organisation for Evacuees PASS BOOK – which details the conditions, facilities and services available to evacuees for their temporary recuperation in Australia. From Dirk Drok’s PASS BOOK, we can see the incoming Dutch were temporarily exempted from the Aliens Registration requirements; that there would be payment of approved medical, dental and hospital expenses; that they had to notify the NIWOE State Officer of their travel plans, for their journeys to be authorised and for their fares to either be paid or refunded. The evacuees were responsible for payment of their own accommodation, otherwise deducted from their allowances.

The Drok family were relatively fortunate as they had already been offered temporary accommodation with friends of the family in Mt Lawley, some four kilometres north of the city. In the late 1930s, Arnold’s uncle (Kitty’s brother who was killed in the early days of the Japanese invasion) had been a boarder at Perth’s Wesley College and during this time one of his classmates was invited to stay with the family in Java for a holiday. This hospitality was then reciprocated when the family arrived as evacuees in 1946.

NIWOE – typically referred to as the ‘Dutch administration’ or the ‘Dutch Club’ – issued clothing coupons which have been a boon for the thousands of evacuees who arrived in Australia wearing the tattered remnants of clothes that had survived the camps. Many were barefoot while others wore make-shift shoes put together from bits of wood and old car tyres. The Drok family PASS BOOK records 127 coupons to a total value of £110 for two adults and o echild to be spent on clothing. They were also given an ‘allowance’ of £80 per month— £65 for Dirk and Kitty, and £15 for Arnold. This was exceptionally generous on the part of the Dutch administration, as 1946 archival records indicate that a man employed by Fairbridge Farm School as a cook for incoming Dutch evacuees was paid £3 5s. per week. It is hardly surprising that many evacuees felt that they had gone from Hell in the camps to Heaven in Perth.

It is also understandable, in the context of the time, that the efficacy and largesse of the Dutch administration would cause friction with the Australian government, trade unions, and servicemen returning from overseas duty. There was an acute accommodation shortage in Australia in the post-war years, and the incoming Dutch were far better placed than the average Australian to secure board and lodging given their very generous allowances.

Most evacuees were able to remain in Australia for eight to ten months before being repatriated to the Netherlands or the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesian Independence was formally secured in1949).

Settlement in Australia

According to the terms of their evacuation to Australia outlined in their NEI PASS BOOK, the Droks were given temporary alien exemption until 28 July 1946.

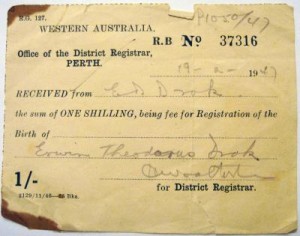

They were, however, among the minority who managed to remain in the country. Arnold is unsure but feels the Mt Lawley family sponsored them as migrants. They moved from Mt Lawley to independent accommodation at 32 Mount Street Perth in a house that since given way to multiple units. Dirk enrolled at the University of Western Australia (UWA) to study languages in 1947, Kitty began to paint china to earn additional money, and two more children were born, Erwin Theodorus Drok in February 1947 and Leonard Paul (known as Paul) in May 1952. The cost of registering Erwin’s 1947 birth in Western Australia was one shilling.

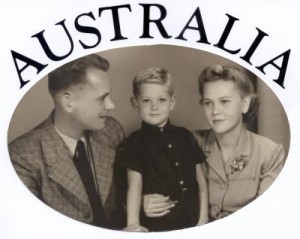

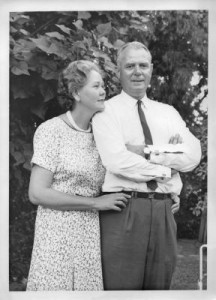

Dirk, Kitty and Arnold recovered well in Australia, which is clearly evident in the photos below taken a year or two after their arrival.

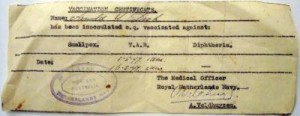

The Dutch administration continued to cover their medical expenses, as shown by a a receipt issued by the Royal Netherlands Navy WA for Smallpox, T.A.B. and Diptheria vaccinations for Arnold in mid-1947.

The Dutch administration continued to cover their medical expenses, as shown by a a receipt issued by the Royal Netherlands Navy WA for Smallpox, T.A.B. and Diptheria vaccinations for Arnold in mid-1947.

Arnold holds some memories of gatherings at the Dutch Club and in later years at family homes where there was a Rijstafel every month. He recalls people reminiscing with others following the meal, being totally uninterested in their wartime conversations, and focusing instead on the Indonesian food. Food to a person who survived internment in a POW camp is very special! He loved it when the gathering was held at the Drok home, as there was enough food left over – including Nasi Goreng and Beef Rendang – to last for a week. He also remembers the St Nicholaas celebration at the Club when he said to his mother: “Hey mum, why is dad dressed up like that?” There was much laughter as he was quickly told to, “Sssh, shssh, shssh”.

Arnold spent three years at Hollywood Primary School followed by Nedlands Primary School and later attended Christchurch Grammar School. He saw himself as Australian and didn’t associate with the Dutch kids. In this respect, he was no different from other Dutch children who grew up in Australia in this time frame. Irrespective, his parents dressed him in traditional Dutch childrens’ clothing for a fancy dress party in Perth in 1945. In the 1949 photo below, Arnold (right) is with his brother Erwin (centre) and family friend Nannette Harvey.

Painter and ceramicist, Kitty Drok

Kitty became a Western Australian painter and ceramicist of note. She was initially taught by artist Grace Nicholls but was largely self-taught, although she was a member of the Western Australian Women’s Society of Fine Arts and Craft and a founding member of what is currently known as the International China Painting Teachers Organisation. In 1961 she became the first porcelain-painting teacher at Fremantle Technical School combining her career as a teacher with studio work and workshops. In the 1970s’ she opens ‘Cynthia’s’ – which sold hand-painted china and paints and oils along with lessons – in the “Grove” shopping complex which had been recently opened off Stirling Highway in Cottesloe.

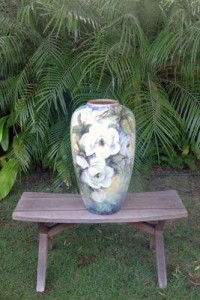

A selection of Kitty Drok’s ceramics, tile and oil paintings

Her special focus was Australian roses and wildflowers, and she was very innovative in mixing paints and oils to get particular shades. She painted on glass and tiles and also with very successful with oil paintings on canvas. Such was her success and reputation as an artist that when Kitty passed away in 2001, Jackson’s purchased her remaining paint stock.

At her 2001 eulogy, the first of her grandchildren – also known as Kitty – spoke eloquently of the impact this remarkable woman made on the family:

- “I guess I knew her best, and the longest out of my generation. And I remember turps, and more colours than I could count. I remember growing up in her studio, surrounded by sunlight, china in all shapes and sizes, and paints. It was fabulous at that age — it felt like a treasure trove, or Alladin’s cave. Oma [grandmother] taught me beauty, and artistic expression … the beauty of a raindrop on a rose, the colours of sunset, the elegance of a particular line. … Fairies existed in Oma’s world. And dragons and flowers. I know this because she painted them for me. Her studio was a timeless place, where I could be free to be myself, and express myself. … And I’d talk to her about the new things she was doing – petit-point, enamelling, metallic paints, bisque paints, white-on-white work. Something new every time. It gave me an appreciation of creativity – that there is always something more to try, always another medium of expression, more ways to see the world”

—Kitty Drok (granddaughter) 2001.

Kitty, the elder, had developed other ways of seeing the world when she developed her artistic flair and sense of parody when interned in Java. The “fairies that existed in Oma’s world” are visible in the sheet made for baby Arnold sometime between 1943 and 1945.

Kitty’s parents, Jo and Herman Uitenhage de Mist-Barkey fitted into the Australian way of life by shortening their name to Barkey. Even Dirk was known as Dick for a number of years. The Barkays moved to Roleystone, with Herman returning to Indonesia on a number of occasions where he went back to the site of the rubber plantation he owned and retrieved Jo’s jewellery carefully hidden within a hollow brick of an outhouse wall. The building was virtually demolished with the exception of one wall – the wall in which the jewellery was hidden. Against the odds he also located the family silver that had been buried on the plantation. It was a remarkable find as the local people left few stones unturned in the knowledge that the majority of plantation owners had buried most of their valuables. Herman passed away in July 1954 at the age of 65 years, and Jo lived to enjoy her first two great grand children (Arnold’s children, Kitty and Michael) and passed away in 1979.

Dirk Drok, helping to uncover the Batavia off the Western Australian coast and key contributor to The Voyage to Disaster

Dirk was a successful mature-age student at UWA, passing many of his examinations in French, German, Greek and Latin with Distinction. He was awarded a Bachelor of Arts in 1950, a Teacher’s Certificate in May 1952, and a Diploma of Education in 1957. He tutored languages at UWA, taught at various schools in regional Western Australia, was elected to the Australian College of Education in 1971, and was Senior Master of Languages, and of Administration, at Christchurch Grammar School from 1973. He lived in Thomas Street Nedlands, and was naturalised, together with Kitty and Arnold, in Perth in 1951.

Dirk also loved history. He worked with Henrietta Drake-Brockman (1901–1968) for a decade to help solve the mystery of the Batavia. Their 1963 publication Voyage to Disaster focuses on the ill-fated voyage of the Batavia in 1629 together with a biography of the ship’s captain Francisco Pelsaert. Importantly it was Dirk’s translations of numerous, relevant documents from the period including Pelseart’s Journal, and the complete Log of the Batavia and of the Gardam – written in the Gothic handwriting of 1629 – that helped Dirk and Henrietta Drake-Brockman to pinpoint the wreck of the Batavia off the Western Australian coast within a mile of their calculated position.[i]

Arnold remembers when the family was living in Boronia Flats opposite the Captain Stirling Hotel in Nedlands. Dirk would be up all night with the projector, with images of Pelseart’s journal – sourced from the Rijks Museum in Amsterdam – projected onto the wall. He took much care in reading and interpreting Gothic Dutch.

In a Letter to the Editor (Western Mail, 2 December 1985) – copies of which are also held in the Battye Library, [ii] National and The Hague Libraries together with a number of Australian university library archives – Dirk states that:

“For a period of ten years I translated aloud to Henrietta who made written notes and together we poured over the current Admiralty Charts locating all the bearings given in relation to both ships. Together we concluded that the ‘Batavia’ must be in the vicinity of Noon Reef, and this decision was not an accident or a guess, it was the result of our arduous search and research. Henrietta told Hugh Edwards of our calculations, so for the next three years local fishermen were on the watch. David Johnson, a crayfisherman, spotted on Morning Reef, objects which he believed to be canons and reported them to Max Cramer then President of the Geraldton Skindivers Club. He and Hugh Edwards visited the site and Max brought to the surface proof that the ‘Batavia’ lay within a mile of our calculated position. Max Cramer, Hugh Edwards and others in conjunction with the Royal Australian navy began uncovering the wreck some five months later. It was then that both Henrietta and I dived on the wreck to view it in situ.”

Western Australia’s Battye Library holds a Memorandum of Agreement, dated 6 September 1962, in which the publisher ‘Angus and Robertson Limited of Sydney’ recognises Henrietta Drake-Brockman and Evert Dirk Drok as ‘joint authors’ of Voyage to Disaster. When the book was first published the following year, Henrietta Drake-Brockman was listed as ‘author’ with ‘all translations from the Dutch and Old Dutch by E. D. Drok’. Five versions of the book were published between 1963 and 1995.

We celebrate Dirk’s contribution to this book and to the finding of the wreck of the Batavia. He deserves a place in the rich history and ongoing exploration and research of this fascinating story.

Dirk was gentle man of the old school, very strict, and a really good teacher—just like his parents and grandparents before him. He taught Latin and French at Christchurch Grammar and then introduced German and Indonesian into the school syllabus. He was also Arnold’s Latin Master at Christchurch, although Latin was not Arnold’s favourite subject. What he did pass onto Arnold was his love of teaching as he is described as a natural at mentoring engineers.

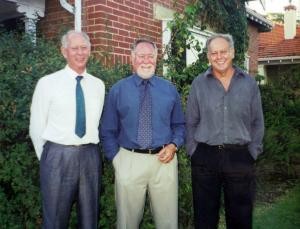

Confinement in a POW camp never held Arnold back. He is a graduate of the University of Western Australia, graduated with a Bachelor of Engineering Degree and later after returning from travel, a Bachelor of Commerce degree. While at the University he represented Western Australia in rowing. He travelled extensively, met his Dutch wife Eline (Engelina) Wajon when working in Switzerland in 1965, married in Holland three years later, returned to Perth in Western Australia and they now have two children and four grandchildren. Today, as a healthy man in his 70s, Arnold teaches kayaking on Perth’s Swan River and also kayaks for pleasure. He continues to think of himself as Australian, considers his experiences of the Pacific War and its memorabilia as history—an interesting history, but something that belongs to a long-gone era. His connection to the past, however, lingers on in the lush greenery of his garden— and he still loves that Indonesian food!

Notes:

[i] Evert Dirk Drok, Letter to the Editor, Western Mail, 2 December 1985. In, ‘Correspondence, 1973–1985,’ Drok, E. D. (Evert D.), ACC 2312A, Battye Library, State Library of Western Australia (SLWA).

[ii] Evert Dirk Drok, Letter to the Editor, Western Mail, 2 December 1985. In, ‘Correspondence, 1973–1985,’ Drok, E. D. (Evert D.), ACC 2312A, Battye Library, State Library of Western Australia (SLWA).

- Writing, interviews, and archival research: Dr Sue Summers, 2014 in consultation with Dirk and Kitty’s son, Arnold Drok.

- Funded by: Your Community Heritage Grants, The Department of the Environment, Canberra.

- Interview Series 2014: organised by Dr Nonja Peters, History of Migration Experiences (HOME), Curtin University, Perth Western Australia.