Records show Dutch were on the first fleet, that the Swan Colony had a Dutch consul as early as 1879 and that Dutch made a living on the land in Queensland in the early part of the 20th century. This tiny portal into the life of Dutch farmers who migrated to Western Australia in 1923 is based on the recollections of Ena and Frances, the two youngest children of Johannes Cornelis Butler, born 1895 at Kapelle, Biezelinge, and his wife Jacoba Mol, who settled on Avon Down farm, Wickepin, some 300 kilometres south-east of Perth, the capital city of Western Australia.

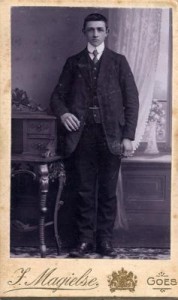

Johannes was educated to tertiary level at Goes agricultural college in the Netherlands. In keeping with the times, Jacoba received only a primary education in preparation for a life as housewife. The Butlers had for generations been blacksmiths who were also latterly engaged in mixed farming; the Mols were established gentry farmers. After their marriage in 1920, and until they migrated in 1923, the young Butlers took over the Butler family’s property in partnership with brother Frank and his wife Maatje. However, they found farming in depressed times, the heavy tax burden and a myriad of controls and restrictions very stressful. It led ultimately to thoughts of emigration. The first to go in 1920 were two unmarried older Butler brothers Adrian and Jan. Why they chose to carve out a new future in Western Australia remains unknown. On arrival they found employment as farm labourers at Toodyay and Kellerberrin. The glowing reports of a life of sunshine, freedom and dry weather prompted Johannes to also consider migration. It was confirmed when his family doctor advised him to move to a warmer climate after constant bouts of pneumonia. Both endured a great deal of ill health while running the family farm. Young and with only one child (Joan, aged eighteen months) in tow, the couple and brother Marinus Butler decided to give Western Australia a trial. Meantime, Frank promised to look after the farm. Peter, Johannes’s educated eldest brother, booked their fares and organised all documentation.

Immigration was the catalyst for Jacoba to change from traditional to Western dress. Before leaving she had only ever worn Zuid Beveland costume. At first, Jacoba felt strange not wearing a hat or cap! However, fittings for her to have a made-to-measure Western wardrobe by Jannetje Guese was an added adventure. In contrast, packing to leave was a fraught activity; deciding what to take and what to leave behind was a constant reminder they would soon leave everything familiar. When the time came to say goodbye, Grandma Anthonina Mol, who was against the move, even refused to bid them farewell; conversely, great grandma Maatje Bruinooge thought it a wonderful opportunity.

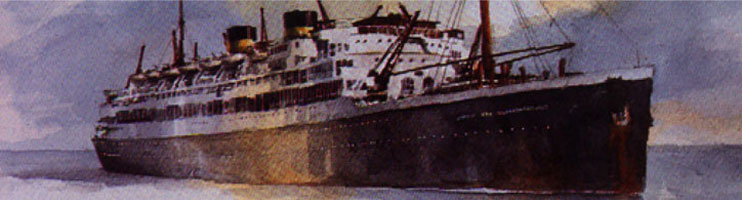

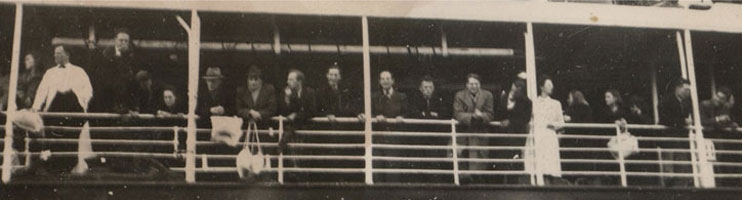

The Butlers went to London by ferry to board the Orient Line RMS Orvietto to Fremantle. The princely cost of £88 only bought them a third-class cabin. The voyage would take them through Gibraltar, Lyon, Naples, Port Said, and Colombo arriving at Fremantle 26 July 1923. Adrian was there to meet them. In Western Australia, Johannes, Jacoba and daughter Joan were to stay at Hillside, the mixed farming property he and Jan had purchased with the inheritance left to them by Grandpa Butler on his death in 1922. It was a tough life, especially for Jacoba. Unfamiliar sand floors, sand fleas (Joan was covered in their bites) and piles of socks to darn and clothes to mend that the bachelors left lying about the house were bad enough, but worse even was the isolation. Jacoba, a chatty person, started to feel quite sad. Despite the difficulties, a year later in July 1924 the couple purchased Avon Downs farm, after discovering the Butler farm in Holland had been sold, which had effectively cut off their escape route back home. Forced to reassess, they opted to stay and to make a go of it. Their decision was greatly helped by Jacoba’s optimistic attitude.

The Butlers went to London by ferry to board the Orient Line RMS Orvietto to Fremantle. The princely cost of £88 only bought them a third-class cabin. The voyage would take them through Gibraltar, Lyon, Naples, Port Said, and Colombo arriving at Fremantle 26 July 1923. Adrian was there to meet them. In Western Australia, Johannes, Jacoba and daughter Joan were to stay at Hillside, the mixed farming property he and Jan had purchased with the inheritance left to them by Grandpa Butler on his death in 1922. It was a tough life, especially for Jacoba. Unfamiliar sand floors, sand fleas (Joan was covered in their bites) and piles of socks to darn and clothes to mend that the bachelors left lying about the house were bad enough, but worse even was the isolation. Jacoba, a chatty person, started to feel quite sad. Despite the difficulties, a year later in July 1924 the couple purchased Avon Downs farm, after discovering the Butler farm in Holland had been sold, which had effectively cut off their escape route back home. Forced to reassess, they opted to stay and to make a go of it. Their decision was greatly helped by Jacoba’s optimistic attitude.

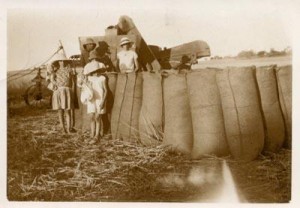

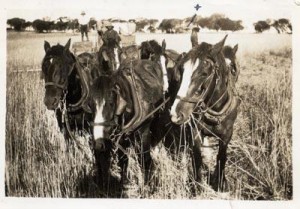

Working with sheep, horses and wheat

The greatest challenge was feeding the family in summer when it was too dry to grow vegetables. Jacoba’s insistence that they purchase a farm with an orchard meant they could at least survive on fruit. Next winter and all the winters that followed they topped-up on home-grown vegetables and also bottled some for use next summer. The family survived by bartering the goods they produced for ones they needed.

The Depression and the birth of two more children Ena (1926) and Frances (1928) meant another 30 years would pass before the title was clear. It also crowded the residence, which had only two front rooms built of solid natural granite stone, a little six-foot veranda at the front and a closed-in veranda at the back. The kitchen doubled as a bathroom and laundry. A bathroom and laundry were added in 1930 from an inheritance left to Jacoba by her grandmother. Jacoba used a coal box iron on the newly laundered clothes, which she had previously dampened down with rain water. If they had used more spring water, which had a higher mineral content, their dental care would have been less costly. By 1928, just before Frances was born, Avon Downs purchased a model T Ford to run Jacoba to Wickepin hospital. The rest of the Butler family from the Netherlands – Peter, Kees, Frank, Maatje, Hanna and Grandma Butler – had by then emigrated and settled on a property in Beverly.

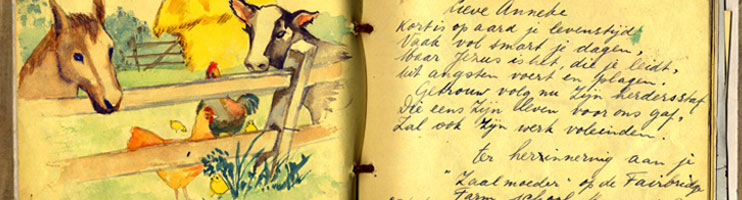

Jacoba ran the family on the same Christian principles on which she had been raised. One such principle was that the family should speak Dutch at home: ‘Another language doesn’t cost anything to carry with you,’ she would say. Ultimately, it helped her children to maintain contact with their relatives in Holland. Sunday was considered a day of rest. Family members would attend local shows, sporting activities, railway picnics, balls, dances or singsongs and once a month the local Presbyterian Church service.

Jacoba relied heavily on the homeopathic book and medicines they bought with them from the Netherlands to treat health problems that emerged. Ena and Frances still have the medicine box with vials.

Schooling was another trial. The farm’s distance from a school meant the oldest children had to board in town from the age of seven. In lieu of board, their parent’s supplied the boarding house with milk, cream, eggs, butter, fruit, and vegetables. Joan and Wim did not like boarding. They were therefore ecstatic when a primary school opened locally in 1932. Joan, Wim and young Ena travelled the six miles there and back in the horse and sulky. However, still being treated as foreigners distressed the children. Ena recalls the teacher ‘couldn’t be fussed about us because she had to really try hard to teach us English and that was not easy’, so her attitude was, ‘If we picked it up, we picked it up, and if we didn’t, so what.’ Country folk did not easily accept newcomers in their midst. The rejection, which impacted on Jacoba and all the children was particularly hard on Joan the oldest, because at school she was often told she was ‘poison’ and isolated on the other side of an imposed barrier in the school shed at lunchtime.

The farm picked up economically during and immediately after the war when prices for wool and wheat soared. A few good seasons, together with the proceeds of contract work and share farming, paid for a new truck and tractor. Wim, then old enough to operate machinery, helped out with contract hay bailing. From then on, life on the farm improved. Even so, in 1946, when Ena went nursing, they were still without a telephone. However, they did have a washing machine and vacuum cleaner that operated on 32-volt power. Now, 60 years later, the farm has passed from Johannes to Wim, who in turn has passed it onto his son Roger.

This story is an extract from an interview Nonja Peters conducted with ENA AND FRANCES BUTLER on 23 June, 2005 at Perth Western Australia.