Anton Roodhuyzen: Memories of life as a child in a Japanese POW Camp in the former Netherlands East Indies

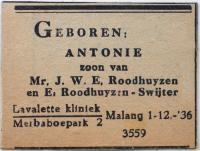

My full name is Antonie Roodhuyzen, a male of European Dutch descent, born 1st December 1936 in the city of Malang, on the island of Java, in Indonesia, then the Netherlands East Indies.

I am a university graduate in art-photography at the Royal Dutch College of Rotterdam. I arrived in Australia in 1988 after 14 years living in New Zealand and have been an Australian citizen since 1996.

My early life in Java was like being in paradise. Of course I didn’t know that when I was just six years of age, like other people this was something I realised far later.

My father, Jan Willem Evert Roodhuyzen, was sent to the NEI by the Dutch government as an assistant tax inspector and was later promoted to Chief Tax Inspector of the island of Java. There were many servants dealing with situations at our places. We had a gardener, a cook, one for the cleaning, and one for the washing only and especially my personal nanny or baboe, as they were called. Her name was Anna, not a special Indonesian name, but I was very fond of her.

Left: The total branch office of the Tax Department in 1939 in Bandoeng. Anton’s father, Deputy Tax Inspector at the time, is seated in the middle of the front row.

Left: The total branch office of the Tax Department in 1939 in Bandoeng. Anton’s father, Deputy Tax Inspector at the time, is seated in the middle of the front row.

One day when I was playing in the front garden, I suddenly saw hundreds of military men marching down the street. I had never seen anything like that before and the amazement is still vivid in my memory. I still recall my mother rushing towards me and dragging me inside against my will as I had wanted to see what was going on.

Then life started to change.

First, my father told us that he would no longer be living at home. He was one of the first to be interned and was sent to Buitenzorg, now known as Bogor. Later he told me that he had to go, because the Japanese erected BIG signs calling upon all Dutch males, 11 years of age and above, to come forward. If they hadn’t, they would have been shot and killed.

At age six, I didn’t fully comprehend what was happening but I do remember my sadness at seeing him off. And I think that we were only able to visit him about three or four times when we found out that he’d been sent away to another camp. We didn’t know where he’d gone and the Japanese refused to give us any information.

Soon after most Dutch women and children were also interned. One of my sisters had Diptheria which proved to be a blessing for the Japanese were scared to death of diseases, particularly those that were infectious. So my mother, my two sisters, and myself were able to remain at home for the next seven months. We were then sent to Camp Karees in Bandoeng and life became quite chaotic. Imagine sharing a big house with 30 other women and children who were all strangers. At least we were sleeping in some form of a bed. Life was difficult and I found the daily quarrels between mothers who were all defending their misbehaving children to be very depressing.

I can’t remember exactly how long we stayed in Karees, but to my knowledge it was not very long before we were summoned by Japanese guards yelling at us to pack our belongings before herding us into a nearby truck. We called them vuil gele erwten (dirty yellow peas) which was our nickname for these intruders. Shortly afterwards we arrived at the train station and were summoned to go into the carriages as quickly as possible. It was already getting dark.

After a three day train trip with many intervals of stopping in the middle of nowhere, we arrived in Batavia (Djakarta) and were then transported in trucks to Tjideng, the most notorious POW camp in the whole archipelago.

Its commander was Captain Sonai – I do hope I have spelt his name right – and he was an absolute lunatic.

Every month, when the full moon was at its peak, Sonai went beserk and in his worst moments he would wound his own soldiers or even beat them to death. The Dutch women were also at his mercy.

He would beat the women up with a kind of bat, and nobody was allowed to take care of them. They had to wait several hours until the coast was clear before they could help, and very often it was too late. Should somebody die, nobody was allowed to touch their bodies, and through the heat of the day the skin of the arms and legs would melt into the asphalt.

This was not a pleasant sight for anyone, let alone a small boy.

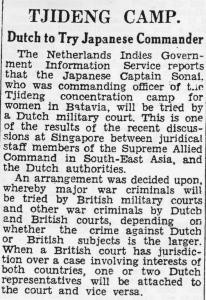

Below: An excerpt taken from The West Australian, 1 December 1945, page 6. Located at the Battye Library in Perth, Western Australia. Sue Summer’s Curtin University-based research with dozens of people incarcerated in the infamous Tjideng POW Camp confirm Anton’s views about the extreme cruelty of this particular camp commander. During his trial by military court Sonai strategically ‘converted’ to Christianity, but this did not help. His war crimes were considered so extreme that he was executed.

Already separated from my father, my mother was then sent to another camp because of an illness. Where did they send her? You guessed it. They wouldn’t tell. Then my eldest sister, who was also ill, was sent to another camp. Destination unknown.

Already separated from my father, my mother was then sent to another camp because of an illness. Where did they send her? You guessed it. They wouldn’t tell. Then my eldest sister, who was also ill, was sent to another camp. Destination unknown.

So I was left with my other sister – who was just 12 years old – who tried hard to be a sister, friend, and mother to me. I was sick also with Bassilaire, Dissentry and Amoeba Dissentry. I do hope I spelled these words right. It’s hard when you lose years of schooling.

For me the war ended, when suddenly, there was plenty of food including bread, flour, sugar and the like. People, who had suffered from years of starvation, started eating themselves literally to death, despite the warnings the doctors gave not to overeat.

A week or so later, I was told that my father had arrived to see us. I went home immediately and there he was. He hugged me, and had tears in his eyes, yet I did not immediately recognise him. It took me a while to get used to having a father again. I know it might sound horrible, but this was the case with many young children.

However, my dad was able to tell me that mum was at the Karolus Hospital in Batavia. So he stole a bicycle from one of the Japanese, and we rode off together, with me sitting on the back of the bike, to see my mother.

At first I didn’t recognise her for she was bloated with oedema. But I was so glad to be with her again for I was always close to her. There was an orphanage right across the road from the hospital which temporarily housed many men, women, and children. It was a blessing to be free again and to be able to walk around without fear of seeing a Japanese soldier.

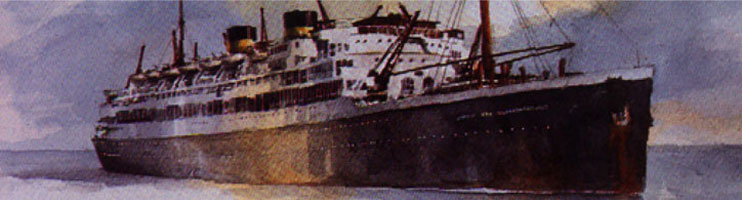

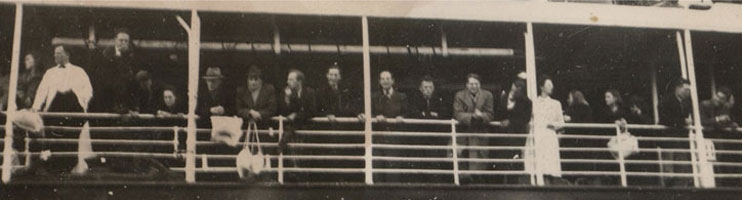

We were among the first to be evacuated from Indonesia in 1945. The day we climbed aboard the Staffordshire at Tandjong Priok in Batavia it was my ninth birthday. I had nothing left to wear except underpants. We were transported to Singapore and then transferred to the Nieuw Amsterdam, a luxury liner which had been transformed to accommodate troops. We had a surprise party welcome us in Suez which took us on a cattle train into the desert. There we found four large halls, that looked a little like hangars, called Vroom en Dreesman, Peek en Cloppenburg, Bijenkorf and C&A.

They turned out to be big warehouses with food and clothing for the cold winder to come. When we arrived in Southampton, I was diagnosed with double-pneumonia, a double mid-ear infection, and measles. So I was transferred from the Nieuw Amsterdam to a hospital ship named Atlantis or maybe Atlantic. I vaguely remember being on that ship with my mother while the rest of the family stayed on the Nieuw Amsterdam.

Our arrival in Amsterdam on 7 January 1946 was far from pleasant. I was ill and it was bitterly cold. And it was the first time I had ever set foot in Holland. A military ambulance brought us to my grandmother’s place at The Hague and I am told I was so ill, and so very close to death, that it was a credit to the good care of my family that I eventually pulled through. But it was nearly a year later before I was allowed to go outside again!

I remember that day so very clearly. It was spring and cool, and I stood in the street, and looked at the houses. They all seemed to be joined together, like in the series of Coronation Street, and I was filled with fear and disbelief. I still vividly remember the words I spoke to myself with my hand on my throat: “Do I have to live here?”

Holland was in a mess itself after the war and many things could only be bought with special coupons. Butter, for example. Many Dutch felt angry towards those who came from the Netherlands East Indies, because we got more coupons and privileges than they did. We were called spijtoptanten. I never found out exactly what that word meant, or where it came from, but they certainly resented our presence when everyone was suffering from food and housing shortages.

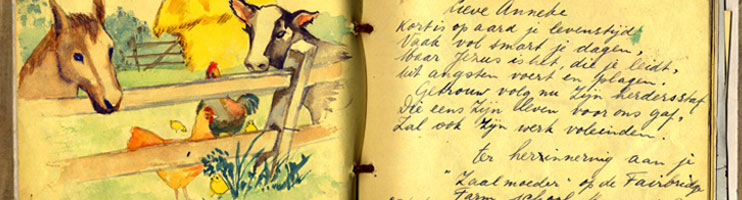

The same year I had to go school. I had never been to one before even though I was ten years old. But I was a bit lucky, for a teacher lady had taught us how to write, read, and to do mathematics when I was in the Tjideng Camp. So with some knowledge, I didn’t have to start quite at the beginning, and was sent to a bridging school where the teachers were very patient with us. It was pretty comforting to be with the same kind of pupils, all out of the Netherlands East Indies.

I was never really attracted to the Dutch society, so after high-school and university I decided to go abroad. It took a while and in 1974 I took the plunge to go to New Zealand and later moved to Western Australia in October 1988. Choosing Western Australia to work and live is like living in a paradise. Different to the Netherlands East Indies, but still a paradise. I keep in contact with my family in Holland and in mid-2006 I spent five months there. Although I am now retired, I was self-employed and had my own business here in Australia, as an advertising photographer.

I would like to describe myself as a Netherlands East Indies (NEI) Dutch, rather than Dutch. I think it is a unique identity, because there were just a small group of us. I even think that the number of Dutch people living in the NEI in the twenties was probably less than 200,000. I have been back in Indonesia many times, mostly to Bali and one time to East Java to visit the house in Malang where I was born. It brought back many memories.

Left: The Roodhuyzen family crest, to the best of Anton’s knowledge, dates back to 1543 in the very small village of Katwijk aan Zee in The Netherlands. The panther-like qualities of the bluish cat are thought to symbolise the strength and power to withstand the wild sea. The helmut symbolises the fighting and defending of the land, while the three wrought iron spears stand for courage,faith and love.

Left: The Roodhuyzen family crest, to the best of Anton’s knowledge, dates back to 1543 in the very small village of Katwijk aan Zee in The Netherlands. The panther-like qualities of the bluish cat are thought to symbolise the strength and power to withstand the wild sea. The helmut symbolises the fighting and defending of the land, while the three wrought iron spears stand for courage,faith and love.

Compiled by: Anton Roodhuyzen and Dr Sue Summers, 2006.