War Story

From ‘The Artist’s View,’ a column written by Petrus Spronk for his local newspaper.

From ‘The Artist’s View,’ a column written by Petrus Spronk for his local newspaper.

Any war does not, as the historians like to have it, run from, let’s say, 1940-1945 as was the case with the WW2, but has reverberations till long after the date. Some to this very day, especially in the psyche of those who lived through it. This is the case for any war, no matter how small or large. War leaves a long black, menacing and dark shadow indeed. It threatens its horribleness well into the period of ‘peace’ and beyond, both in reality and nightmarish dreams. It’s not at all a matter of a few plane/tanks/soldiers in and out and done. So before we get involved in anything like it again we may just consider that aspect of it.

Four miniature pictures from the other side of war

Imagine a little boy of about five, the age things are beginning to be remembered. Imagine him, one fine day, walking hand in hand with his mother. They are walking in a street. There is a war on. The mother is just pointing out the blossoms blossoming into spring and the buds bursting into leaves when a soldier stops them in their tracks and forces them around a corner. A lot of people, huddled into a group, are already gathered there. After a while the little boy manages to let go of his mothers hand and work himself into the front of the gathering. He wishes he had not done this. The forced accidental gathering is made to watch ten arbitrarily chosen people from the neighbourhood (hey, that is John the grocer, what is he doing there?) being lined up, face the gathering, and get shot in the head in cold blood. Pavement justice for the killing of a Dutch informer. A lifetime memory. Yet it was a sunny spring day in May.

Imagine the same boy a year or so later. He is still living in a war zone. He has become just a little more street wise and seems to recognise one of the soldiers, who shot his friend the grocer, cycle by. In an instant the boy yells something obscene, now the language of the streets, after which the soldier turns his bike and goes after him. The little boy gets away through a series of alleyways and for days, panic stricken, refuses to come out from behind the couch. Does not want to play on the street anymore.

Next door to the little five year old boy’s house is another house. In it lives his friend, a little girl of the same age. One night the boy is yanked out of bed. It is very dark. He remembers this as his very first memory. He is firmly held under someone’s arm and ran, down steep stairs, into the cellar. This cellar comprises of a long cold passage with a few small spaces off it on either side. From one of the spaces, a dark hole, a few wooden boxes are fetched. This very moment is etched in the little boy’s impressionable mind as horrific, and stays there. The wooden boxes are lined up against the wall in the passage and the assembled people sit down to await the onslaught. The fear is palpable. The light flickers and goes out. The area is bombed. Terrifying whistling sounds followed by deep vibrating explosions. They go on for, what seems, a long while. One explosion particularly strong. A local hit. Anxious wait till morning. The house next door has been hit. A huge hole now allows the boy to look inside his friend’s house without going to visit. No one was hurt, which was just a matter of degrees.

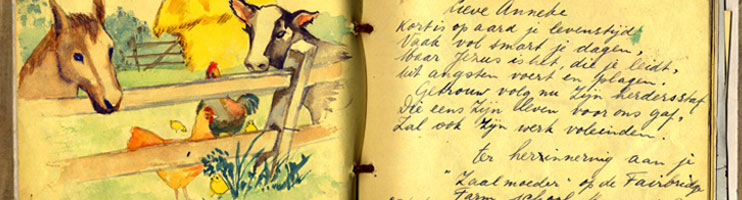

A few weeks later the little girl from the bombed house is invited on a country summer camp. These events are organised despite the war. Compassioned people are still compassioned people. This camp is for children who have suffered as a result of the war. Like the little boy’s little girl friend having her home/privacy/safety and spirit bombed. The bus travels east into rural Holland and in one particularly beautiful flowered spot is strafed, then bombed. All the children die. Including the little boy’s friend. An innocent six year old girl.

The little boy witnesses other things which are frighteningly unusual. As the result of the shooting of a soldier, there is no door-to-door search for the killer. Justice is meted out immediately and with great effect. Across from the point the soldier has been shot, and killed, a block of houses is pinpointed with a general movement of another soldier’s arm. A group of foot soldiers is dispatched to this block of flats, houses, homes, memories of intimacy, etc – hammers on doors and tells the bewildered occupiers that they have 10 minutes to get out. The little boy remembers many people with hand carts walking, crying in a sad slow procession, carrying the few things they could quickly grab together. They were lucky to have been warned. The whole block of houses, flats, siting rooms, bedrooms, kitchens, places of intimate memories and family histories are torched. As a memory to this event, there existed for many years a large scorched empty black block of land, on which occasionally a small bunch of flowers would appear.

Less important but just as intense. At any time of night and or day, there is banging on doors. Nothing is subtle. Foreign soldiers come in, look around, peer, push and prod, commit crimes of privacy and worse. Just at their own behest. People out of control, controlling others. At the same time there are many more much softer knockings on doors. A continuous parade of starving people asking for a slice of bread.

During five years the little boy’s father went underground. Actually he went under and above ground, since all this time he lived between two floors. Entrance under a suitcase in a cupboard. A very cramped living space. However, a better then real prison. A hiding place once nearly given away, innocently, by the little five year old boy.

There are no photographs of these memories. They are not needed. These particular images live on graphically, vividly, both in the mind, and in the countless other wars, with much the same events, minimal variations, the same images played over and over and over.

Before we get involved again, may we stop, reflect and consider. There are thousands of people for which this constant terror is, and has been, a daily experience for a long time now. When, one may well ask, is enough, enough?

How shall we live?

23 October 2002