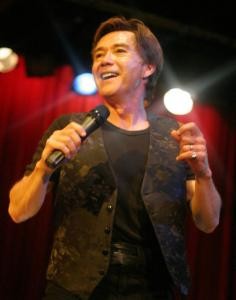

Marty Rhone

Entertainer and singer

- Born: Karel van Rhoon, Surabaya in Java, Indonesia, 7 May 1948

- Year of arrival in Australia: 1950

- Arrival: Qantas Constellation.

- Now living: Sydney

- Awards and recognition: Gold record for recording ‘Denim & Lace’; Winner, Outstanding Performance Award at World Popular Song Festival, Tokyo 1976; FAMI Fellow of the Australian Marketing Institute; Certified Practising Marketer CFRE; CertifiedFundraising Executive Member of the Fundraising Institute of Australia. Three AMI Awards for Marketing Excellence including: National Award for ‘Desperate & Dateless Ball’; FIA National Special Event of the Year 2002 for ‘Corporate Countdown’ and FIA National Special Event of the Year 2006 for ‘ROCKINC’

Popular Australian entertainer Marty Rhone began life as Karel van Rhoon in the former Netherlands East Indies. His father Eddy van Rhoon was of mixed Dutch and Chinese heritage and his mother Judith (nee Bagshaw) was fifth generation Australian. Together, they gave Marty a rich and wonderful heritage: he is one-quarter Dutch-Indonesian, one-quarter Chinese, and one-half Australian.

Marty is well known to Australian audiences as a popular singer and entertainer, but his personal and family history is equally as interesting.

During the Pacific War (1942-1945), Marty’s father was in the Dutch Navy, flying as navigator on the Catalina amphibious aircraft based in Surabaya. He was taken as a prisoner of war to the Burma Railroad and then forced to work on the wharves in Tokyo, Japan. During his time there he learned of the bombings at Nagasaki and Hiroshima and also told Marty about the US warplanes that flew continuously overhead often dropping their leaflets and bombs in his vicinity.

At war’s end Eddy was repatriated back to Indonesia and then visited Sydney for an extended furlow with a large contingent of Dutch East Indies airmen and navy personnel.

Like Marty, Eddy van Rhoon was a musician of some note. He was a jazz pianist who very quickly entered the Sydney music circle, meeting the newly-emerging singer and actress, Judith Bagshaw, who was also an acquaintance of legendary Australian jazz musician, Don Burrows.

This was 1947. Eddy was 29 years of age and Judith had just turned 17. She came from a large, close-knit, extended family that had been graziers in New South Wales since the 19th century.

The family quickly drew Eddy into their midst for they were keen – like many other Australians during the war years – to extend hospitality and goodwill to visiting servicemen who had helped to defend the south-west Pacific, including Australia.

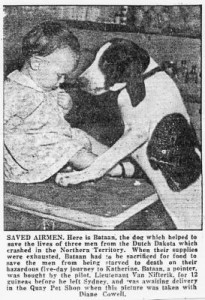

There followed a brief courtship between the two, but Eddy had to return to Indonesia, as he was still a serviceman with the Dutch Navy. On the flight to Indonesia, Eddy’s plane crashed near Kakadu in the Northern Territory with eight crewmen on board. It was Front Page news as two other fighter planes had come down in Queensland at the same time. Marty still has the newspaper cuttings, but the name of the newspapers and the dates were not retained. (He thinks they were possibly from the Sydney Morning Herald or the Daily Telegraph. See photo below plus links: one, two, and three. )

Despite extensive searches, Eddy’s plane could not be found. The plane’s radio was inoperable after the crash and Eddy set out into the Australian outback with a number of other crew members in search of help. They took the inflatable dinghy and also the dog ‘Bataan’ that had been an unofficial crew member on the flight to Indonesia.

They were in the midst of Kakadu in the Northern Territory where cattle stations were often larger than the size of Holland or England, and where locating a town or a homestead was like finding a needle in a haystack.

Eventually they came across the Kathryn River, inflated the dinghy, and rode with the current until it swept them into the Kathryn Gorge.

Today this journey is part of Marty’s family folklore:

Today this journey is part of Marty’s family folklore:

“You know, crocodiles, the whole works,” he said. “Of course, they did not know where they were going, they did not quite know how to survive, and when they had run out of food they ended up having to eat their dog to survive. So it was quite an epic journey.”

Some ten days later, Eddy and the crew stumbled across the remote town of Kathryn, where: “They sort of just walked into the police station and said, ‘We’re the missing Dutch airmen’. Of course, the local police said, ‘You’re kidding!’ And they were all dishevelled and hungry and probably a little flea bitten and rather the worse for wear.”

This was also a harrowing time for Judith, yet she had a strong and firm belief that Eddy and the rest of the crew would be found. She thought the Australian Airforce was remarkable for she was kept informed of everything that was going on.

She vividly remembers sitting by the phone waiting for even the smallest piece of news and then finally the call that told her Eddy was alive and well in the Australian Outback.

After recuperating Eddy rejoined the Dutch navy in Indonesia, but was able to return to Australia within a few months where he and Judith were married at St Luke’s Church at Vaucluse, Sydney on 12 April 1947.

Judith then accompanied Eddy to Surabaya in Indonesia, where his unit was based.

Marty was born there in 7 May 1948 and recalls many stories that his mother and father told him about this critical point of time in which Indonesian forces were fighting for their independence from the Dutch while The Netherlands was struggling hard to retain its influence in the Indonesian archipelago.

His parents told him that it was a very uncomfortable and dangerous time to be Dutch and to be in Indonesia.

Marty: “And this groundswell was obviously coming up and reached a head in 1950. Part of the reason for the animosity is that of course the Dutch were very much like all colonial powers and had Indonesians as servants; you know, lived a pretty good life, and were waited on hand and foot by Indonesians. You know the Dutch were hanging out, holding out, and life in the services went on. And so dad was taken away from the house- hold a lot and there was only mum and myself. It was a very unstable period. It must have been tough for mum. Interestingly enough, according to mum and dad, the servants were very loyal. At one time they actually hid mum and myself in a cupboard when some infiltrators broke into the house. They were highly protective of the family.”

In spite of the turmoil, Judith loved her time in Indonesia. She learned to speak Malay and found the Indonesian servants “very helpful, very loyal, and very charming”. In her opinion, if it was not for the servants, the family may not have survived.

Marty: “I suppose if you look at it in purely economic terms it was a better life for many of the servants that they would otherwise have had. And that’s the great Catch 22. But of course every country wants its independence and to be self reliant and self-sufficient That’s not to say that in some instances they didn’t have a tough time with the Dutch. Like most colonial countries do. But it’s not black and white. There’s good and bad on both sides. In the end, the word went out to just get out quick, don’t worry about your belongings, just get out, because your life depends on it. I think I recall mum and dad saying it was a Qantas plane, a Constellation. That was the evacuation. Mum indicated that it was fairly chaotic. She said there were just people at the airport and planes flying constantly.”

They had the choice of going to Australia or The Netherlands.

They had the choice of going to Australia or The Netherlands.

But as Judith was Australian-born, and Eddy was used to a warmer climate, the family decided to come to Australia. Marty clearly remembers living at the Sydney bayside suburb Brighton Le Sands when he was just four years of age.

Yet the family did not stay there long for in these early years their lives were shaped by a series of small and large migrations.

“It was really a nomadic life,” he recalled. “And I can remember with mum and dad we were forever on the move . We spent some time in Brisbane, we flew to Darwin, and then came back to Sydney for a short time, and then Dad bought a car in Sydney. It was a Czechoslovakian car, which was called a Skoda, and we drove – all of us with my grandmother in the back of the car – via Adelaide, South Australia, where we had relatives, and then to Darwin. We were very nomadic for a time. And we made a number of trips from Darwin to Sydney because our links were with Sydney, and Adelaide. But we were a little family unit living in Darwin.”

Eddy, who had been displaced and expelled from his country of birth, had never been to The Netherlands and decided that the weather and the ambience of Darwin was about as close as he could get to his earlier life on the Indonesian islands.

This was 1953 and he quickly found a job as a wireless operator with Northern Territory’s Department of Civil Aviation.

Marty, who was just five years old at the time, clearly remembers how this small city evoked another era:

“There was so much around Darwin that was reminiscent of how life was during the Second World War. That’s a distinct memory for me. Buildings with rooves blown off still in the same state of disrepair as when Darwin was bombed. The Darwin Hotel had pockmarks on the walls where Japanese aircraft had strafed it; the exterior walls of the [original] Commonwealth Bank were also pockmarked with bullet holes. There were steel crosses on the beaches to stop amphibious craft coming up, and there were the wrecks of the ships in the Harbour. It was all still there. And this was 1953, eight years after the war. It was quite surreal. As a very young child it meant nothing to you. ‘Hey look mum, look at that building: it’s all wrecked, it’s all razzed’. And it was almost as if it had happened that year. That’s a vivid memory for me.”

When the van Rhoon family first moved to Darwin they lived in the military huts at Nightcliff in the old semi-circular, corrugated-iron Nissen huts that had been used by the servicemen in World War II. He remembers they were basic but quite habitable. Yet the corrugated-iron increased the heat and the humidity and, during the ‘wet season’, when there were tropical storms, the water would run throughout the hut.

One time he awoke in the middle of the night and found himself stepping into ankle-deep water as the rugs floated down the hallway.

One time he awoke in the middle of the night and found himself stepping into ankle-deep water as the rugs floated down the hallway.

When the military huts were dismantled, Eddy and Judith found alternative accommodation at the old Flying Boat Base at Darwin Harbour. (For photos, click on link to: Northern Territory Library and Information Service. If you wish to explore further, search the Australian War Memorial Website.)

The Flying Base held vivid memories for five-year-old Marty:

“Now one family – husband, wife and child – were living at the old Flying Boat Base and there were about 24 toilets. You couldn’t believe how many toilets there were! It was an old Flying Boat Base and we were actually living there. Alone. Down on the water. It was an adventure, you know. Life was an adventure. I remember Darwin as being a lot of fun. But my mum hated it when she first went there. She hated the heat, the mosquitoes. She hated the sand flies. But she grew to love it and today she said it was the happiest time of her life. But dad loved it because, during the evenings he was also playing as a professional musician. His band was called ‘Eddy van Rhoon and his Tropical Knights’. And I can remember their musical stands had palm trees.”

Marty recalls that his father was “the number one muso in Darwin” during the 1950s and a “genuinely fine jazz pianist. A very, very good jazz pianist. He ended up playing with Winifred Atwell quite a few years later here in Sydney as her dinner accompanist. You know when you wanted a night’s entertainment, ‘Eddy van Rhoon and his Tropical Knights’ were the band to get with dad on the piano, a drummer, a saxophonist and the old tea chest base. The old tea chest, they used to have a string though it, and they were quite amazing and that was life in Darwin in those days. Darwin was the last frontier in those days for the Australians. Right through the ’50s it was the last frontier.”

There is no doubt that life in Darwin presented a portal to an earlier time of Australian history: it was a different atmosphere, a different era, untouched by the transport and media revolution that re-shaped Australia in the latter part of the 20th century.

Yet as Marty notes it was also an adventure, and his father was happy there for he’d grown up in a similar kind of atmosphere where life was very relaxed: “Dad had the psyche of a laid back, relaxed islander, and in a society like Australia where the emphasis is very much on getting ahead, and forward, and a little bit ambitious, and ruthless, all of that, and dad wasn’t like that.”

Eddy probably never realised his aspirations yet it never seemed to bother him. He assimilated as well as he could into Australia, but he was “a little bit of a square peg in a round hole” given his mixed Dutch-Chinese appearance and very broad accent. Both Eddy and Marty were subject to much racism – a very negative aspect of Australian life at the time, particularly in Darwin.

In the context of the time, they had little defense for their Dutch heritage was invisible to the Australian community, while their mixed cultural background was there for all to see.

According to Marty, “We both experienced it. Dad experienced it and I experienced it. When I first started school, I remember being called ‘Ching Chong Chinaman’. Yeah, there was racism in Darwin. There was racism against the Aborigines, and there was racism against the Chinese I think Australia’s a little bit of a contradiction. It’s a very tolerant society, but it’s still a very racist society. The racism is still there.”

According to Marty, “We both experienced it. Dad experienced it and I experienced it. When I first started school, I remember being called ‘Ching Chong Chinaman’. Yeah, there was racism in Darwin. There was racism against the Aborigines, and there was racism against the Chinese I think Australia’s a little bit of a contradiction. It’s a very tolerant society, but it’s still a very racist society. The racism is still there.”

Marty’s Australian-born mother had a different journey.

She had hated the Darwin heat but learned to love this little city that was one of the last reminders of Australia’s colonial past.

Yet Judith was also a very fine jazz vocalist and actress in her own right. She belonged to the Darwin Musical Comedy Society and performed in the ‘Mikado’,’For Me and My Gal’, and in other Gilbert and Sullivan musicals.

Marty loved and absorbed it all: “I had a father who was a good muso and I had a mother who sang and so I always had music around me – I had a rich musical childhood.”

It was from watching his mother performing in musical comedy that Marty developed a burning desire to become a performer. He loved going to the opening nights, loved sitting in the audience and, before long, he was up there with them on stage singing jazz!

Eddy tried to teach Marty the technical side of being a performer and gave him lessons on the piano. While this proved to be a disaster, Eddy was nonetheless instrumental in getting his son into Show Biz!

He got his son his first gig at eleven years of age when he sang at the Boy Scout Jamboree in the Darwin Town Hall while Eddy accompanied him on the piano: “I think the bug really hit me after I performed that first time in Darwin, and I really built up this desire to be an entertainer from a very young age”.

In 1960, after seven years in Darwin, the van Rhoon family decided to return to Sydney. Marty had completed his primary schooling, Judith was missing her family, and it was felt that there would be more opportunities for the children, and for their education, in a larger city.

This was important as Marty now had a sister and brother (Kymn who was born on 7 March 1958 and Martin born on 17 March 1960).

And so they left behind the Darwin ‘atmosphere’ that had shaped Marty’s formative years. Eddy was also leaving behind a lifestyle as a ‘big fish in a small bowl’ and although he was happy that he’d been able to make a good life for himself and his family, his life was never the same for him in Sydney.

“It was not just a physical migration for dad, but one that had much emotional significance. He was a product of the islands, and I don’t think you could take the island out of dad.”

His brother and sister, in contrast, were too young to remember their time there.

Sydney had attracted thousands of migrants from The Netherlands, and the former Netherlands East Indies, yet the van Rhoon family did not keep ties with the Dutch community. With a mix of Dutch, Indonesian and Chinese heritage they also found themselves at the receiving end of racism from much of the Dutch-Australian community. Eddy’s brother, repatriated to The Netherlands in 1946, experienced much the same thing there. It was the children who were better able to blend into the host cultures.

Sydney had attracted thousands of migrants from The Netherlands, and the former Netherlands East Indies, yet the van Rhoon family did not keep ties with the Dutch community. With a mix of Dutch, Indonesian and Chinese heritage they also found themselves at the receiving end of racism from much of the Dutch-Australian community. Eddy’s brother, repatriated to The Netherlands in 1946, experienced much the same thing there. It was the children who were better able to blend into the host cultures.

Life in Sydney proved to be wonderful for Marty. He went on the Tarax Show – a live talent show for children – hosted by King Corky who was the television idol of Australian children during the 1960s. Marty won second place when he was just 13 years old. From this came a permanent position with ‘Desmond Tester’ and ‘Miss Penny’ on ‘Kaper Kabaret’, a popular afternoon children’s show on Channel Nine. He was then given a singing engagement every three weeks, which made him ‘a bit of a celebrity’ at his local school, Crows Nest Boys High.

His desire to become part of the entertainment industry continued to grow and he released his first single ‘Nature Boy’ in 1966. By the end of the 1960s his name had become a household word throughout Australia.

In 1975 Marty’s ‘Denim and Lace’ burst into the charts and remained there for 35 weeks, becoming the second-biggest selling single of that year. He followed that up with another No.1 hit in 1975 with ‘A Mean Pair of Jeans’.

His interests also extended to theatre and he performed in the original Sydney season of Godspell in 1972-73. He then went to England to try his luck and performed with Yul Brynner at the London Palladium in The King and I from 1979-80. In 1988 he worked with the late Pope John Paul II as the MC at his Youth Rally in Sydney and, in 2007, had been a singer and entertainer for some forty-one years:

“I’ve worked in many parts of the world,” he said. “I’ve just had a great career. And the roots of that can go right back to Darwin. That’s where it all started. That’s where the urge was built.”

“I’ve worked in many parts of the world,” he said. “I’ve just had a great career. And the roots of that can go right back to Darwin. That’s where it all started. That’s where the urge was built.”

Currently, Marty has two parallel careers: one as an entertainer, and another in charity fundraising. He was Fundraising Director for the Australian Red Cross (NSW), General Manager Fundraising & Development with the Spastic Centre of NSW and Fundraising Manager for a number of years with Alzheimers Australia (NSW).

He is today an independent fundraising consultant and performs regularly in clubs and for corporate events. In recent years he started ‘The Entertainer’s Studio’ where he helps teach: “Up and coming young performers how to develop their stagecraft and how to engage with audiences because they don’t get the same opportunities of live performances that we used to get. So a lot of them are flying blind. They’re singing well, and performing – but the only way they can learn is from a video. And that doesn’t tell you a great deal. Live performances tell you a great deal, but there just aren’t the venues around. So I’m teaching that as well, so it keeps me busy.”

Today Marty lives in the northern suburbs of Sydney.

He married Italian born migrant Rosa Merola on 31 January 1976 in Melbourne. They have two children: Luke born on 11 August 1980 and Mathew born on 25 January 1985.

Together, Marty and Rosa have given their children an interesting heritage as they are one-quarter Australian, one-eighth Dutch-Indonesian, one-eighth Chinese and one-half Italian. Yet the children know little of their heritage, of their past, as life at the present time seems to be asking more interesting questions.

Marty, however, is very aware of his Dutch-Indonesian and Chinese heritage. He finds the historical link ‘fascinating’ but does not perceive a personal or emotional connection with this aspect of his past. When young, he denied his Chinese heritage. He had to, it was self-protective.

But today he’s proud of his history and is very aware that the Dutch who were left in the Netherlands East Indies after the war quickly became a forgotten group of people: “That’s why I find it so interesting that you’re doing this study”.

Would you like to know more about Marty’s career? Then click right here.

Compiled: February 2007 based on an interview by Dr Sue Summers with Marty Rhone in Sydney, mid-2005.